Until that time, laws had been a combination of whatever custom, tradition and the ruling judge (always a Patrician) decided. Nobody could even know if they were being treated fairly by the law because nobody knew exactly what the law was. Terentilius wanted the laws to be written down to give greater protection to all.

The Patricians eventually (in 450 BCE) agreed to the Plebian demands request. A group of 10 men, known as the Decemvirate were selected to draw up the laws. According to Livy the 10 men went first to Greece to study Athenian laws and those of other cities.

On their return the men of the Decemvirate drew up their laws, which were written on 12 bronze tables placed in the forum, so that they were accessible to all.

The tables themselves were destroyed and we only know some of what they contained from later sources. But we do know that they focused mainly on civil laws between private citizens, including land ownership rights, inheritance rights and damages. They also included some religious laws. The worst punishment (the death penalty) was reserved for those who corrupted the legal system — judges who took bribes and witnesses who gave false testimony.

Rome was not the first state to have written laws, but these tablets were influential for generations. They formed the basis of Roman law for centuries after and Roman students were taught to memorize them in school. In fact, these laws influenced the men who drafted the US Constitution and also form the basis of common law which is still part of our legal system today.

This foundation of the Roman legal system was compiled some 900 years after the Ten Commandments were given to the Israelites, according to the Torah’s chronology. But some 600-900 years before our record of how the Rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud viewed the Ten Commandments and their place in the Jewish legal system.

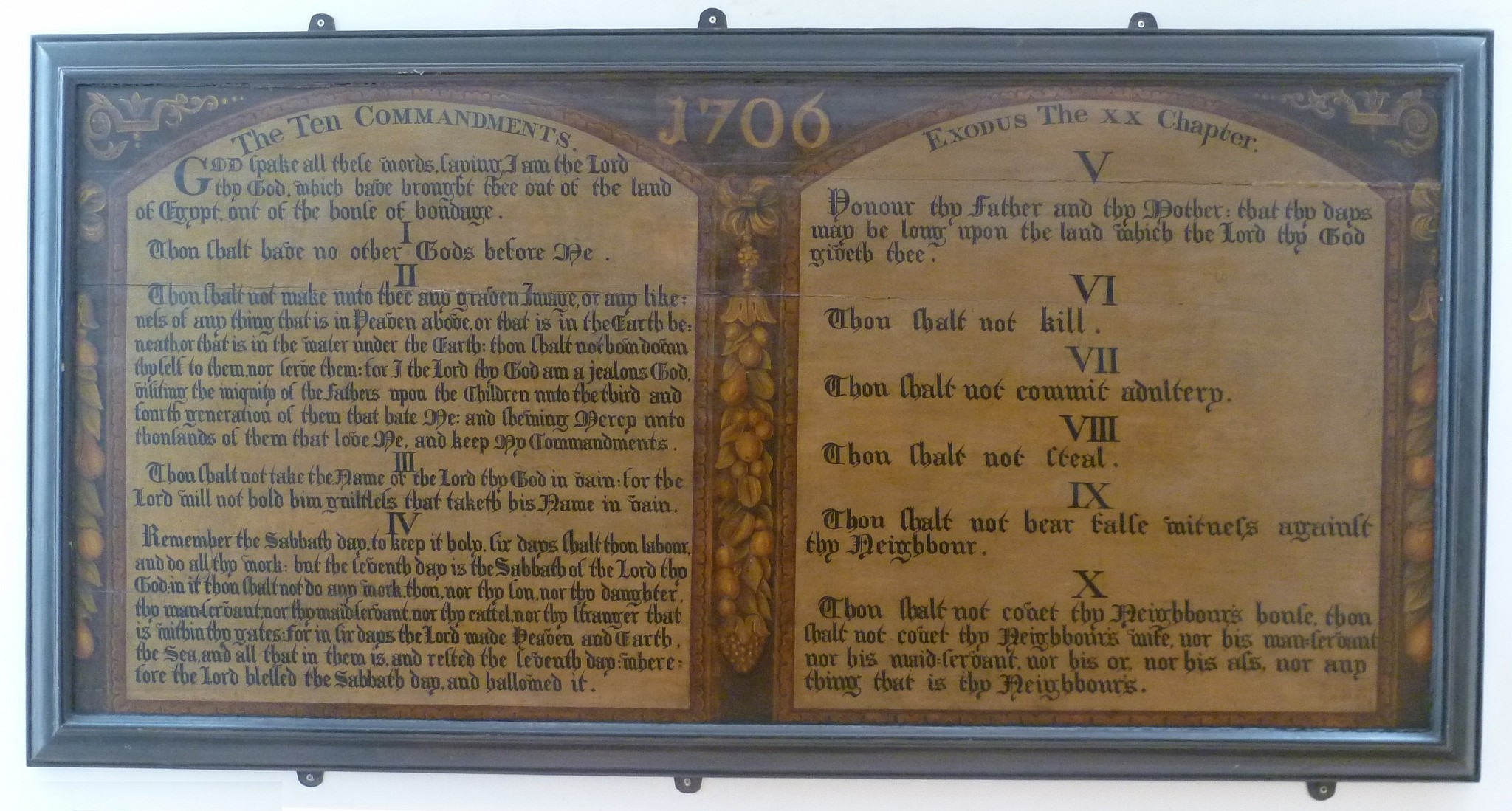

In contrast with the Twelve Tables, which were placed publicly in the Forum for all to see, the two tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments were sealed in the Ark of the Covenant, which was never opened. The Ark itself was hidden away in the holiest part of the Tabernacle (and later the Temple) and only seen on one day of the year by only one person (the High Priest). In the Second Temple era the Ark was no longer there, having been either placed in a hidden and forgotten chamber deep within the Temple,or taken to Ethiopia by Solomon’s son.

The Twelve Tables came at the insistence of the people and were drawn up by a group of men. The Torah describes how the Ten Commandments were given by God and not only were they unasked for but according to rabbinic tradition the Israelites has to be forced to accept them.

The contrast between these two foundations of legal system is stark but the truth is that the prophets and rabbis removed virtually all meaning from the Ten Commandments.

Many of the prophets railed against the Jewish people for not observing the Torah and for not behaving correctly. None of them mentioned the Ten Commandments specifically in their criticisms of the people (though they did complain that the Jews were not keeping various commandments included in the Ten, along with other commandments that were not being kept).

Then the third century sage Rabbi Simlai stated (Makkot 23b) that the Israelites did not receive 10 commandments at Sinai but 613. (Medieval rabbis who listed the 613 all agreed that the number of Torah laws is actually far higher than that, and there are even more rabbinic laws). The Talmud (Makkot 24a) then lists other rabbis who seek out the most essential Commandments, reducing the list from 11 until eventually deciding on the single commandment of, “The righteous shall live by his faith,” (Habakkuk 2:4). None of the rabbis thought that the classic 10 were the most essential laws.

Not only did the rabbis ignore the Ten Commandments when listing the most essential laws but they also redefined them to remove their plain meaning. For example, “Do not steal,” (Exodus 20:12) is interpreted to mean “Do not kidnap” (Sanhedrin 86a). Theft is still biblically forbidden but is not one of the Ten.

Others, like the commandments to observe the Sabbath or honor one’s parents have become the subjects of vast collections of intricate laws which go well beyond (and sometimes contradict) the plain meaning of the words.

By the mishnaic period the Ten Commandments were reduced from a legal code to a prayer in the daily service (similar to the Shema). But then, in response to the rise of Christianity, the rabbis removed the Ten Commandments from prayer too (Berachot 12a).

So although representations of the Two Tablets appear in synagogues and court rooms, the Ten Commandments are virtually insignificant as a legal code.

Unlike the Roman tablets which are almost forgotten yet still impact our laws, the Ten Commandments are extremely well known, yet have very little influence on the Jewish legal system.

No comments:

Post a Comment