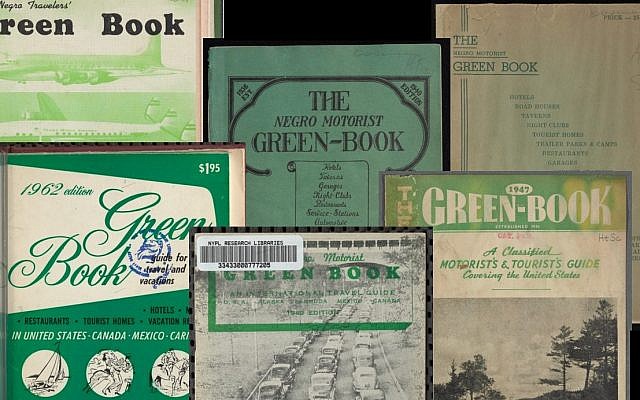

The movie’s title comes from an annual directory published by and named for Victor Hugo Green which listed hotels, stores and gas stations that welcomed African Americans. The full title of the directory was “The Negro Motorist Green Book” and it was published every year from 1936-1966. The guide, which was almost forgotten over the decades, was essential in the era of racial segregation, enforced by legislation known as the Jim Crow laws.

These laws, upheld by the Supreme Court, maintained racial segregation in all public facilities in the southern states of the US. The court ruled that Jim Crow did not violate the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution — which ensured equal protection” to all people — by invoking the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made racial discrimination illegal, but until that time the Green Book was a valuable guide for African-American motorists at a time when the relative low cost of motoring meant that many Americans took to the roads, especially those looking to escape the racism and segregation they experienced on public transport.

However, driving across America was not easy for people of color when many gas stations, hostels, restaurants and stores refused to serve them. Even finding a public bathroom was sometimes difficult. Many African-American travelers were forced to pack not only food for their journey, but also carry spare fuel and sometimes even a portable toilet. And if the car broke down, it was sometimes almost impossible to find a mechanic who would fix it for them. There were also thousands of so-called “sundown towns,” which barred non-whites after dark (one of which features in the movie).

This was why Green’s guide became invaluable. In the introduction to the 1949 edition he wrote, “With the introduction of this travel guide in 1936, it has been our idea to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.”

Green was a postal worker from Harlem, New York, and he published 15,000 copies of his guide each year. He said the inspiration for his guide came from similar Jewish publications.

The Jewish press has long published information about places that are restricted and there are numerous publications that give the gentile whites all kinds of information.

Jews continued to face discrimination when Green launched his guide, though the peak of anti-Semitism in the US was in the 1920s. That decade may have heralded in the age of motoring, but the American father of the motorcar, Henry Ford, was an avowed anti-Semite who blamed the Jews for World War I (and for almost everything else). In 1924, the government passed the Johnson–Reed Act, effectively severely limiting immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe. The Ku Klux Klan, newly reformed in 1915, claimed 4-5 million members by the 1920s. Hatred of Jews in America was widespread.

In response, Jews created their own philanthropic societies, their own hotels and resorts, their own lobbying groups, and their own guides to where Jews were welcomed. By the 1960s, Jews were at the forefront in the fight against discrimination of all kinds, and were among the founders and early funders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

According to a PBS show, Jews were at the heart of the fight against Jim Crow.

The American Jewish Committee, the American Jewish Congress, and the Anti-Defamation League were central to the campaign against racial prejudice. Jews made substantial financial contributions to many civil rights organizations, including the NAACP, the Urban League, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. About 50 percent of the civil rights attorneys in the South during the 1960s were Jews, as were over 50 percent of the Whites who went to Mississippi in 1964 to challenge Jim Crow Laws.

Jews knew that those who discriminated against minorities were the same people who hated Jews. The Jews of American felt that standing up for minorities was not only the right thing to do morally, but also the best way of combatting anti-Semitism.

The truth is, however, that anti-Semitism, the hatred of Jews, began millennia ago, in an incident we read in this week’s Torah portion.

After the Israelites miraculously left Egypt, everyone thought they were invincible. The Torah describes how they split the Red Sea, defeated Pharaoh’s army, and were guided by a column of fire and a pillar of smoke. Nobody in their right mind would have challenged the Israelites at the peak of their power.

Yet along came the tribe of Amalek and attacked the people, as they wandered through the desert. “And Amalek came and warred with Israel in Rephidim” (Exodus 17:8).

Amalek was not threatened by the Jews, who were heading to the Land of Canaan. The Jews had no resources that Amalek wanted or needed. How did their leader inspire the Amalekites to fight what must have seemed a suicidal war? Did he encourage them to fight by claiming that the Israelites were “criminals, drug dealers, and rapists” (or whatever was the equivalent at that time)? What other methods did he use to get his supporters to destroy themselves in order to get rid of the Israelites?

Amalek fought against the Israelites for no reason other than a hatred of Jews. Their war with Israel was the precursor to an eternal war against the Jews fought by those who hate Jews, as the verse states (Exodus 17:16):

He said, ‘For his hand is on the throne of God, there is a war between God and Amalek from generation to generation.’

Amalek was one single tribe that were wiped out thousands of years ago. But Amalek’s spiritual heirs, who continue to hate the Jews, remain strong to this day.

In 1948, Green wrote, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

Things have improved in so many ways in the US for minorities, but there is still a long way to go. Though discrimination based on race is now illegal, hatred of minorities is still widespread on social media and political rhetoric. The Green Book is no longer published and is almost forgotten. But the hatred of those who are different in the color of their skin, their religion or their ethnicity remains strong in some circles.

The last line of the introduction in the 1937 edition of the Green Book states, “Let’s all get together and make motoring better.” This message is equally relevant now, though I would alter it to read, “Let’s all get together to make the entire world better.”

—

With thanks to the wonderful podcast 99% Invisible for the inspiration behind this d’var Torah.

No comments:

Post a Comment