According to many medieval Jewish sources no species of animal can ever become extinct. This was mainstream belief, held by (and shaping policy for) many of the world leaders up until the 19th century. In this class we discuss extinction, the reasons why it presents difficulty to theologians, and how damaging religious convictions can be when they fly in the face of the evidence. Also, the raven was right.

Here is the source sheet:

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Expecting the Messiah

Here is an audio recording of one of the classed I gave a Limmud Scotland last month. I've entitled it "Expecting the Messiah" and it is about the dangers of predicting details of the Messiah's arrival.

Here is the source sheet:

Here is the source sheet:

Sunday, June 02, 2019

Parshat Bamidbar -- Happy Birthday Al Capone

One dark Chicago night in 1926, Fats Waller was leaving his regular gig at the Sherman Hotel when he was surrounded by four armed men. Waller was one of the most popular jazz musicians of his time, and one of the most prolific composers. But he had no idea what was about to happen.

One of the armed men shoved a pistol into Waller’s ample belly and told him to get into the limo. Fearing for his life, the pianist did as he was told. He was driven out of town, down to Cicero. The car pulled up outside the Hawthorn Inn and Waller was led inside, gun still pointed at his back, and told to sit down at the piano and start playing.

As he looked around him, Waller realized that he was at a birthday party for the infamous Al Capone, who had relocated his headquarters to Cicero, where he had a better deal with officials, police, and rival gangs than he had had in Chicago. Capone was turning 27 and Fats Waller was a surprise birthday present from “the boys.”

In 1926, America was in the grip of prohibition, and as a result, Capone was at the height of his power. It was still three years before the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, after which he was dubbed “Public Enemy Number One.” It was five years before Capone was sent to jail for tax evasion, where he would serve eight years of an 11-year sentence, including time in Alcatraz, and just over six years after that, aged 48, Capone would be dead.

Al Capone, after his arrest in 1930 on vagrancy charges. (Public Domain, Chicago Bureau of the FBI/ Wikimedia Commons)

But 1926 was a great time to be alive. Capone was head of a massive crime organization following the “resignation” of Johnny Torrio, who had been shot several times. The Chicago Outfit ran an illegal brewery and transportation network that reached across the border to Canada. Several establishments that refused to buy their alcohol from the Outfit were mysteriously blown up, leading to an estimated 100 deaths.

Ironically, though several of Al’s brothers worked with him in the alcohol business, his older brother Vincenzo Capone changed his name to Richard James Hart and became a prohibition agent in Homer, Nebraska. There, he orchestrated a series of successful raids against bootleggers, which earned him the nickname “Two-gun” Hart.

Capone’s reign as head of the crime gang also saw an increase in the number of brothels in Chicago. Yet despite his ruthless violence against rivals and others, Capone gave large donations to charity and earned a reputation as a modern-day Robin Hood.

In addition to a penchant for the ladies, Capone liked wearing fancy suits, and enjoyed expensive cigars, gourmet food and drink. He was also known for wearing flashy and flamboyant jewelry. And he loved to party.

So, when his henchmen were trying to come up with a present to give their boss for his 27th birthday, they could think of nothing better than bringing him Fats Waller, one of his favorite musicians.

Waller played at gunpoint for three days, entertaining the mafia boss and those who were celebrating with him. But the pianist loved to party almost as much as Capone did, especially as after every song he received large cash tips and drinks. By the time he stumbled out of the Hawthorn Inn, Waller had thousands of dollars in his pockets and had developed a taste for fine champagne.

He also had a watertight excuse if he were ever questioned by the FBI — he could honestly claim he had no ties to the mob boss. Waller never played for Capone again, but continued touring until 1943, when he died of pneumonia, aged only 39. At his funeral, the pastor who eulogized him praised Waller, saying he “always played to a packed house.”

The story of Capone and the kidnapped musician got me thinking about how difficult birthdays are. Not only is it hard to find the right present for someone (after all, not everyone can have Fats Waller at gunpoint), but also how tricky it is to actually keep track of birthdays.

The earliest recorded birthday was that of Pharaoh, described in Genesis 40:20. As part of the celebrations, Pharaoh restored the chief butler to his position and executed the chief baker. However, it is possible that this was not actually the anniversary of Pharaoh’s birth, but rather the anniversary of his coronation. Many Pharaohs were believed to be deities once they ascended the throne, and thus it may mark his “rebirth” as a god.

The Palermo Stone in Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo. (G.dallorto/ Wikimedia Commons)

We know from the Palermo Stone that the ancient Pharaohs celebrated a feast called “Appearance of the King” every two years, on the anniversary of their coronation. Is it possible that this is what Pharaoh was celebrating? Perhaps that explained the strange Hebrew phrase “yom huledet et par’o” rather than the simpler “yom huledet par’o” that we would use in modern Hebrew.

You see, until recently it was rather difficult to know when someone’s birthday was. Until modern record keeping, most people didn’t know the day they were born. A friend of mine, who came to Israel with his parents from Morocco as a child, recently turned 70. But nobody knows exactly when. When his mother and father arrived in Israel, they did not know his date of birth. In Morocco, there were no birth certificates at that time. So the official documents list his birthday as 0/0/1949.

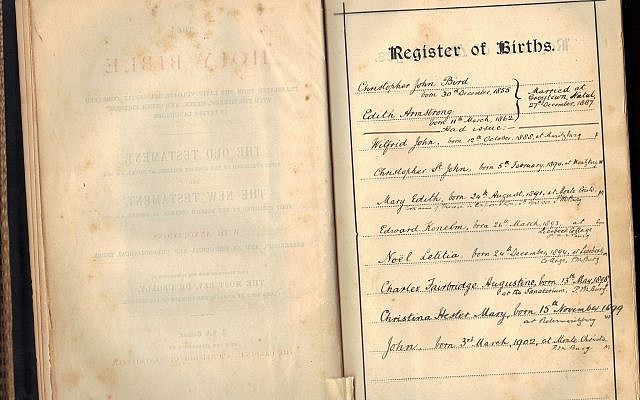

The modern practice of compulsory registration of births only started in the United Kingdom in about 1853. In the United States, it was only introduced in 1902. On September 2, 1990, the Convention on the Rights of the Child came into force. It was accepted by 191 countries, and gives children the right to a registered name and nationality at birth.

Bird family birth registry from Bird family bible. (CC BY-SA, Theobird/ Wikimedia Commons)

But before that records were kept sporadically. Some countries, even in ancient times, registered births for tax purposes. In some places, births were registered in local parishes or synagogues for religious reasons. Often, families would record births and deaths in prayer books or elsewhere. But there was no systematic documentation of a child’s date of birth.

It is possible that even in ancient times, parents looked at the stars when their child was born to know what his or her future had in store according to the astrologers. Thus, we find in the Talmud (Shabbat 156a) that one who is born under the sign of Mars will shed blood. So he will become a blood-letter, a thief, a ritual slaughterer, or a mohel (circumciser).

It is a much more difficult thing to pinpoint the exact date of a birth and know how to celebrate it a year later.

And knowing the length of a year is even more difficult. Nowadays, we celebrate secular birthdays and anniversaries according to the Gregorian calendar, which we note is (approximately) the time it takes for the earth to make one full orbit of the sun.

Earth orbiting the sun. (CC BY-SA, kristian fagerström/ Flickr)

But before the Israelites left Egypt, they were given a brand-new calendar — in fact the very first commandment they were given was to mark the first of Nisan as the beginning of the year. Of course, back then the month was not called Nisan — the names of the “Hebrew” months are Babylonian, and were introduced to the calendar during the Babylonian exile (see Ramban on Exodus 12:2). Before that, the months were called by the Torah “first month,” “second month,” “third month,” etc., although it seems from the book of I Kings (6:1 and 8:2) that they had other names too, such as “Ziv”’ and “Eitanim.”

But the new months they were given means that they now had a new way of calculating a year. It wasn’t the passage of the earth around the sun, but the completion of 12 (or sometimes 13) new moons.

Even if someone knew exactly on which day they were born, it is unlikely that they would also be able to calculate back to work out when their birthday fell according to this new calendar. For one thing, without seeing all the previous moons and without a Sanhedrin to declare the new month, it would have been impossible to know the length of any particular year.

So, although nowadays we take it for granted, it is worth noting that in this week’s Torah reading (Numbers 1:1-3), Moses, along with the leaders of each of the tribes, was instructed to count every man over the age of 20.

God spoke to Moses in the Sinai wilderness in the tent of meeting, on the first day of the second month in the second year after they left the land of Egypt, saying: Count the head of the entire congregation of the Children of Israel, according to their families and their father’s houses, by the number of names, a headcount of each male. From 20 years old and upward…

How would they know which of the men were 19 and a half and which were over the age of 20? They had just left years of slavery in Egypt and record-keeping was probably not high on their list of things to do.

We know that the tribe of Levi was counted from the age of 30 days. This solves the problem of record-keeping, but requires parents to note exactly the time of day the baby was born (because if the child was born after dark it would be already the next day, and if he was born during sunset, it is even more complicated). Also, it would have been unseemly for Moses and Aaron to enter the tents of women who had recently given birth. Therefore, several commentaries, including Kli Yakar and Ohr HaChaim, explain that Moses and Aaron would stand outside the tent and a heavenly voice would proclaim how many children over the age of 30 days were inside.

So, it is possible that miracles were also involved when they were counting all the men over the age of 20. Perhaps they had some sign by which they knew who had already had their respective birthdays and who was still a few days away.

Or perhaps they didn’t need to count precisely. Maybe anyone who was approximately 19 when they left Egypt was considered to be 20-years-old one year later.

Or maybe the confusion about birth dates explains the discrepancies in the number of men at the different times they were counted in the wilderness.

Birthdays are on my mind this week. I don’t think we should celebrate them in the same way that Pharaoh or Al Capone celebrated. But birthdays are a time to thank your parents for bringing you into existence. And they are also a good time for an annual stock-taking — while the earth has been traveling at about 107,000 kilometers per hour (67,000 miles per hour) around the sun, how far have we actually come as individuals?

Monday, May 13, 2019

Parshat Emor — Confronting death

Today, Amherst, Massachusetts, is a medium-sized town 80 kilometers (50 miles) from Boston, home to over 40,000 people. But in the 19th century, Amherst was a quiet, unremarkable town, with a much smaller population which, over 100 years, doubled in size from 2,500 to 5,000.

For such a small town, it was home to a significant number of people who made a huge contribution to the world — the poet Robert Frost taught and retired there; Noah Webster, of the eponymous dictionary, lived there; Melvil Dewey, devised the Dewey-Decimal classification system while an assistant librarian in Amherst College; P. D. Eastman, born in Amherst, served in World War II in the Signal Corps film unit, under Theodor Geisel — better known as Dr. Seuss — and went on to illustrate many of his books; the actress Uma Thurman was born and raised in the city.

But for me, the most important resident of Amherst is Emily Dickinson. She was born there in 1830, though she didn’t really become famous until after her death in 1886. During her lifetime, she was better known as a gardener and published fewer than a dozen poems — most of which were modified to conform with a more traditional style.

On her deathbed, Dickinson told her younger sister Lavina to burn all her papers. Luckily for us, Lavina ignored the instruction to destroy the 40 or so notebooks, and instead published the collection of almost 1,800 poems her sister left behind.

Town Hall, Amherst Massachusetts. (CC BY, John Phelan/ Wikimedia Commons)

Dickinson left school at 16, having spent her final year of formal education in Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, in a class of 30 categorized religiously as “without hope.” She was considered eccentric by her neighbors, and from the time she was 30 she mostly lived the life of a recluse, seldom going out of her bedroom, corresponding with her few acquaintances through letters.

But she was never alone. Death was her constant companion, as it was for most Americans in the 19th century.

Even though New England had one of the lowest mortality rates in 19th century USA, the average life expectancy was about 46. During Dickinson’s lifetime, the percentage of children who died before their fifth birthday dropped from over 40 percent to below 30% — still a huge number by modern Western standards. And over 600,000 men died during the Civil War, estimated to be about 10% of all Northern men aged 20-45 and over 30% of white Southern men between the ages of 18-40.

So everyone in the United States knew death intimately. But Dickinson embraced Death as a friend and companion.

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

Her poetic style and themes were non-traditional, to say the least, and faced critical reception when they were first published. Thomas Bailey Aldrich wrote in the Atlantic Monthly in January 1892 that,

“It is plain that Miss Dickinson possessed an extremely unconventional and grotesque fancy… The incoherence and formlessness of her — versicles are fatal … an eccentric, dreamy, half-educated recluse in an out-of-the-way New England village (or anywhere else) cannot with impunity set at defiance the laws of gravitation and grammar.”

But her poetry resonated with the public. The first volume of her poetry, published four years after her death, went through 11 editions in just two years. Many people were able to connect with and relate to Dickinson’s descriptions of death, loss, immortality and despair.

It was not Death, for I stood up,

And all the Dead, lie down –

It was not Night, for all the Bells

Put out their Tongues, for Noon.It was not Frost, for on my Flesh

I felt Siroccos – crawl –

Nor Fire – for just my marble feet

Could keep a Chancel, cool –And yet, it tasted, like them all,

The Figures I have seen

Set orderly, for Burial

Reminded me, of mine –As if my life were shaven,

And fitted to a frame,

And could not breathe without a key,

And ’twas like Midnight, some –When everything that ticked — has stopped –

And space stares – all around —

Or Grisly frosts – first Autumn morns,

Repeal the Beating Ground —But most, like Chaos — Stopless – cool –

Without a Chance, or spar —

Or even a Report of Land —

To justify — Despair.

Although there are many new and horrible ways in which people die or are killed, nowadays, thanks to modern medicine, hygiene and nutrition, most people in the Western world rarely have to deal directly and personally with death on the scale that our grandparents did. I have many friends who had never attended a funeral until they were in their 20s or 30s. But just a few decades ago, before the discovery and manufacture of penicillin and vaccines, everyone knew death only too well.

This week’s Torah portion begins with restrictions placed on the priests, the descendants of Aharon, known in Hebrew as kohanim. In addition to restrictions on whom they may marry, they are also warned against coming into contact with the dead. Apart from close relatives, priests must keep well away from death. Not only are they forbidden to enter cemeteries, but they may not even be in the same room or under the same roof as a corpse.

The traditional explanation for the extra holiness required of them is that the priests were traditionally the teachers of Torah. The verse states, (Malachi 2:7)

For the lips of the priest guard knowledge, and they should seek Torah from his mouth, for he is an angel of God of Hosts.

As guardians of the Torah and angels of God, they had to keep far away from impurity. This idea of the priest as an angel was most vividly embodied in Simeon the Just, who served as High Priest in the Second Temple for 40 years. The Talmud relates that before Alexander the Great came to Israel in 332 BCE, Simeon appeared to him in a dream and predicted his victory. Alexander had wanted a statue of himself placed in the Temple, but, instead, Simeon promised that all sons of priests born that year would be named Alexander (Leviticus Rabba 13).

The detail of the Alexander Mosaic showing Alexander the Great. (Public Domain./ Wikimedia Commons)

I wonder if there is another, psychological, reason that the Torah insists that priests keep far away from human death. During Temple times, the main task of the priests (at least for the weeks that they were on duty) was to slaughter sacrifices.

Every day, dozens, or sometimes even hundreds or thousands, of animals were killed by the priests, the blood sprinkled and the animals dismembered and burned on the altar (though most of the meat was actually eaten by the priests and those who brought the sacrifices). The priests would spend their days barefoot, wading through the blood which sometimes came up to their knees.

High priest offering a sacrifice of a goat, on the Day of Atonement,; from Henry Davenport Northrop, Treasures of the Bible, published 1894. (Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

I remember many years ago, helping supervise the kosher slaughter in New Zealand. I was standing alongside the non-Jewish workers who were removing and sorting the hearts, livers, kidneys and other organs from the chickens, and occasionally ripping off the heads if the machine wasn’t working properly. Though each time, when I first walked into the room, I was an emotional wreck, within a few minutes, I was tossing the carcasses along the line like they were rugby balls.

And I wondered, how was it possible for men and women who spent every day working on the production line dismembering animals to clock out at the end of the day and go out to the pub with their mates, or go home to their families and forget about the death they were surrounded by every day. How could they switch off their emotions and slide back into regular life?

Is it possible that the Torah placed stringent restrictions on the priests to keep far away from human death to constantly remind them of the difference between animals and humans? Because the priests were animal slaughterers and butchers, they had to have extra stringencies to remind them of the importance of human life (and death).

However, even though a priest was forbidden to deal with the body of anyone other than a close relative, there was one case when he was required to personally bury a body.

If a priest (or anyone) came across a body with nobody to take care of it, he had to personally bury the corpse to ensure its dignity. The laws of purity were cast aside in the face of giving a human being a proper funeral.

Washing, dressing, and preparing a body for burial is referred to by the rabbis as chesed shel emet — the true kindness. It is literally a thankless task, motivated solely by concern for those who are unable to help themselves.

The priest, normally kept distant from death, shows the true holiness of life, through this mandated exception to perform this ultimate kindness for others.

Sunday, February 03, 2019

Parshat Mishpatim: Let Them Eat Cake

In his inaugural electoral speech on Tuesday night, Benny Gantz compared the current Israeli government to King Louis XVI, implying that the country is in danger of heading towards a revolution.

“The basic values of Israeli statehood have been converted into the mannerisms of a French royal house,” Gantz said. Instead of serving the people, the government looms over the people and finds the people to be a bore.”

It is impossible to pinpoint a single cause that led to the storming of the Bastille, the overthrow of Louis XVI and the guillotining of thousands in the Reign of Terror presided over by Maximilien Robespierre. But let’s look at a few of the main issues that led to the French Revolution.

While the wealthy clergy and nobility were exempt from paying taxes, a crippling tax burden was levied on the common people (known as the Third Estate) through a variety of direct and indirect taxes. The 100,000 clergy, who owned 10% of the land, along with the ruling classes living in their grand homes, were exempt from most of those taxes.

Adding to the pressure on the lower classes was the deregulation of the grain market, which led to increasing bread prices and often dire food shortages (prompting Queen Marie-Antoinette to allegedly utter her infamous line, “Let them eat cake”).

The Enlightenment spreading across Europe further undermined the authority of the church and the king.

In addition, most of the population of 26 million had a sense that the king and his court cared little for the people he was supposed to be ruling. Versailles, built by Louis XIV to demonstrate France’s greatness to the world, became a symbol of the king’s apathy for his subjects. Some have estimated that Versaille sucked up almost 10% of the national treasury.

The country was already on the verge of bankruptcy after fighting the Seven Years’ War, when the Kingdom of France led a large coalition of forces against Britain and its allies, and involved most of Europe. France then challenged Britain in the new world spending millions of dollars in support of the American Revolutionary War.

As a result of these wars, France’s debt spiraled out of control, ballooning from 8 million livres to well over 13 billion. Attempts to levy taxes on the upper classes were rejected by the nobility. Eventually, King Louis appointed Jacques Necker who initiated a policy of taking huge international loans rather than trying to balance the budget.

Ultimately, Necker was ousted and the Sun King appointed Charles de Calonne to run the country’s finances. He knew that the only way to balance the books and avert the revolution was to impose taxes on the upper classes, but when Louis convened the Assembly of Notables to hear the dire situation and Calonne’s proposals, they blocked his efforts and refused to pay their share of the national burden.

Calonne tried to borrow money to keep the country afloat, but by this time none of the international banks or money lenders would take a risk on a country in economic free-fall.

Necker had borrowed millions at high interest rates and the country had no way of paying back the loans. The populace — starving, ignored and influenced by the radical new ideas of the enlightenment — eventually rose up against the monarchy, with the rallying cry of, “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” (Freedom, equality, fraternity).

This week’s Torah portion, Mishpatim, contains more laws than almost any other. One of those laws is the prohibition of taking interest on loans (Exodus 22:24).

In an agrarian society, a person needed a loan to feed the family when the crops failed or needed to borrow money to buy animals or grain to raise for the coming year. Lending money was a form of charity and charging interest could be crippling.

However, as Jewish society transformed from the biblical vision of working the land to the commercial society of a nation evicted from its land, the nature of loans also changed. A business loan was not saving someone from starvation but an opportunity for growth and development. A scarcity of money to borrow would have stunted the economic development of society and the country.

For this reason, the rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud found a “loophole” which was in fact within the spirit of the law. Although charging interest remains prohibited, a wealthy person could “invest” in a business opportunity in exchange for a share of the profits. This is known as “heter iska” and remains the underlying basis by which banks in Israel lend money to this day.

It is important to distinguish between a business, which relies on commercial loans to create wealth, and a loan to an individual without a livelihood who needs the money to put food on the table. In one case it is permitted (and perhaps even encouraged) to lend money with interest. In the other, it is completely forbidden.

The thing about history is that it is only seen looking backwards. Even on his deathbed in 1715 Louis XIV could never have imagined the possibility of a revolution, nor could his great-grandson Louis XV who succeeded him. By the time his grandson Louis XVI realized the discontent of the nation and the danger the monarchy faced it was too late for him to do enough to avert the revolution.

A quote attributed to Mark Twain says that history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. The Torah portion teaches that if someone is starving, loan them the money interest-free to buy cake. And if they are looking to expand their cake-making operation, invest in their business.

—-

(Note: As anyone with a passing knowledge of European history is aware, Jews were only forbidden from charging interest to other Jews. But they were allowed to charge interest on loans to gentiles. The Church, which barred Christians from charging interest to other Christians, exploited this, encouraging Jews to become money lenders. This no doubt fueled anti-Semitism (we’ve all heard of Shylock), but also encouraged religious or political leaders to persecute Jews to avoid repayment.)

“The basic values of Israeli statehood have been converted into the mannerisms of a French royal house,” Gantz said. Instead of serving the people, the government looms over the people and finds the people to be a bore.”

It is impossible to pinpoint a single cause that led to the storming of the Bastille, the overthrow of Louis XVI and the guillotining of thousands in the Reign of Terror presided over by Maximilien Robespierre. But let’s look at a few of the main issues that led to the French Revolution.

While the wealthy clergy and nobility were exempt from paying taxes, a crippling tax burden was levied on the common people (known as the Third Estate) through a variety of direct and indirect taxes. The 100,000 clergy, who owned 10% of the land, along with the ruling classes living in their grand homes, were exempt from most of those taxes.

Adding to the pressure on the lower classes was the deregulation of the grain market, which led to increasing bread prices and often dire food shortages (prompting Queen Marie-Antoinette to allegedly utter her infamous line, “Let them eat cake”).

The Enlightenment spreading across Europe further undermined the authority of the church and the king.

In addition, most of the population of 26 million had a sense that the king and his court cared little for the people he was supposed to be ruling. Versailles, built by Louis XIV to demonstrate France’s greatness to the world, became a symbol of the king’s apathy for his subjects. Some have estimated that Versaille sucked up almost 10% of the national treasury.

The country was already on the verge of bankruptcy after fighting the Seven Years’ War, when the Kingdom of France led a large coalition of forces against Britain and its allies, and involved most of Europe. France then challenged Britain in the new world spending millions of dollars in support of the American Revolutionary War.

As a result of these wars, France’s debt spiraled out of control, ballooning from 8 million livres to well over 13 billion. Attempts to levy taxes on the upper classes were rejected by the nobility. Eventually, King Louis appointed Jacques Necker who initiated a policy of taking huge international loans rather than trying to balance the budget.

Ultimately, Necker was ousted and the Sun King appointed Charles de Calonne to run the country’s finances. He knew that the only way to balance the books and avert the revolution was to impose taxes on the upper classes, but when Louis convened the Assembly of Notables to hear the dire situation and Calonne’s proposals, they blocked his efforts and refused to pay their share of the national burden.

Calonne tried to borrow money to keep the country afloat, but by this time none of the international banks or money lenders would take a risk on a country in economic free-fall.

Necker had borrowed millions at high interest rates and the country had no way of paying back the loans. The populace — starving, ignored and influenced by the radical new ideas of the enlightenment — eventually rose up against the monarchy, with the rallying cry of, “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” (Freedom, equality, fraternity).

This week’s Torah portion, Mishpatim, contains more laws than almost any other. One of those laws is the prohibition of taking interest on loans (Exodus 22:24).

"If you lend money to My people, the poor among you, do not be like a money-lender, do not charge him interest."

In an agrarian society, a person needed a loan to feed the family when the crops failed or needed to borrow money to buy animals or grain to raise for the coming year. Lending money was a form of charity and charging interest could be crippling.

However, as Jewish society transformed from the biblical vision of working the land to the commercial society of a nation evicted from its land, the nature of loans also changed. A business loan was not saving someone from starvation but an opportunity for growth and development. A scarcity of money to borrow would have stunted the economic development of society and the country.

For this reason, the rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud found a “loophole” which was in fact within the spirit of the law. Although charging interest remains prohibited, a wealthy person could “invest” in a business opportunity in exchange for a share of the profits. This is known as “heter iska” and remains the underlying basis by which banks in Israel lend money to this day.

It is important to distinguish between a business, which relies on commercial loans to create wealth, and a loan to an individual without a livelihood who needs the money to put food on the table. In one case it is permitted (and perhaps even encouraged) to lend money with interest. In the other, it is completely forbidden.

The thing about history is that it is only seen looking backwards. Even on his deathbed in 1715 Louis XIV could never have imagined the possibility of a revolution, nor could his great-grandson Louis XV who succeeded him. By the time his grandson Louis XVI realized the discontent of the nation and the danger the monarchy faced it was too late for him to do enough to avert the revolution.

A quote attributed to Mark Twain says that history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. The Torah portion teaches that if someone is starving, loan them the money interest-free to buy cake. And if they are looking to expand their cake-making operation, invest in their business.

—-

(Note: As anyone with a passing knowledge of European history is aware, Jews were only forbidden from charging interest to other Jews. But they were allowed to charge interest on loans to gentiles. The Church, which barred Christians from charging interest to other Christians, exploited this, encouraging Jews to become money lenders. This no doubt fueled anti-Semitism (we’ve all heard of Shylock), but also encouraged religious or political leaders to persecute Jews to avoid repayment.)

Wednesday, January 23, 2019

Parshat Yitro: The 12 Tables

The Roman Plebians were sick of being abused by the Patricians and demanded more power in governing the city. Around 462 BCE Terentilius — who was the Plebian Tribune at the time — advocated for a written set of laws that would govern Roman citizens.

Until that time, laws had been a combination of whatever custom, tradition and the ruling judge (always a Patrician) decided. Nobody could even know if they were being treated fairly by the law because nobody knew exactly what the law was. Terentilius wanted the laws to be written down to give greater protection to all.

The Patricians eventually (in 450 BCE) agreed to the Plebian demands request. A group of 10 men, known as the Decemvirate were selected to draw up the laws. According to Livy the 10 men went first to Greece to study Athenian laws and those of other cities.

On their return the men of the Decemvirate drew up their laws, which were written on 12 bronze tables placed in the forum, so that they were accessible to all.

The tables themselves were destroyed and we only know some of what they contained from later sources. But we do know that they focused mainly on civil laws between private citizens, including land ownership rights, inheritance rights and damages. They also included some religious laws. The worst punishment (the death penalty) was reserved for those who corrupted the legal system — judges who took bribes and witnesses who gave false testimony.

Rome was not the first state to have written laws, but these tablets were influential for generations. They formed the basis of Roman law for centuries after and Roman students were taught to memorize them in school. In fact, these laws influenced the men who drafted the US Constitution and also form the basis of common law which is still part of our legal system today.

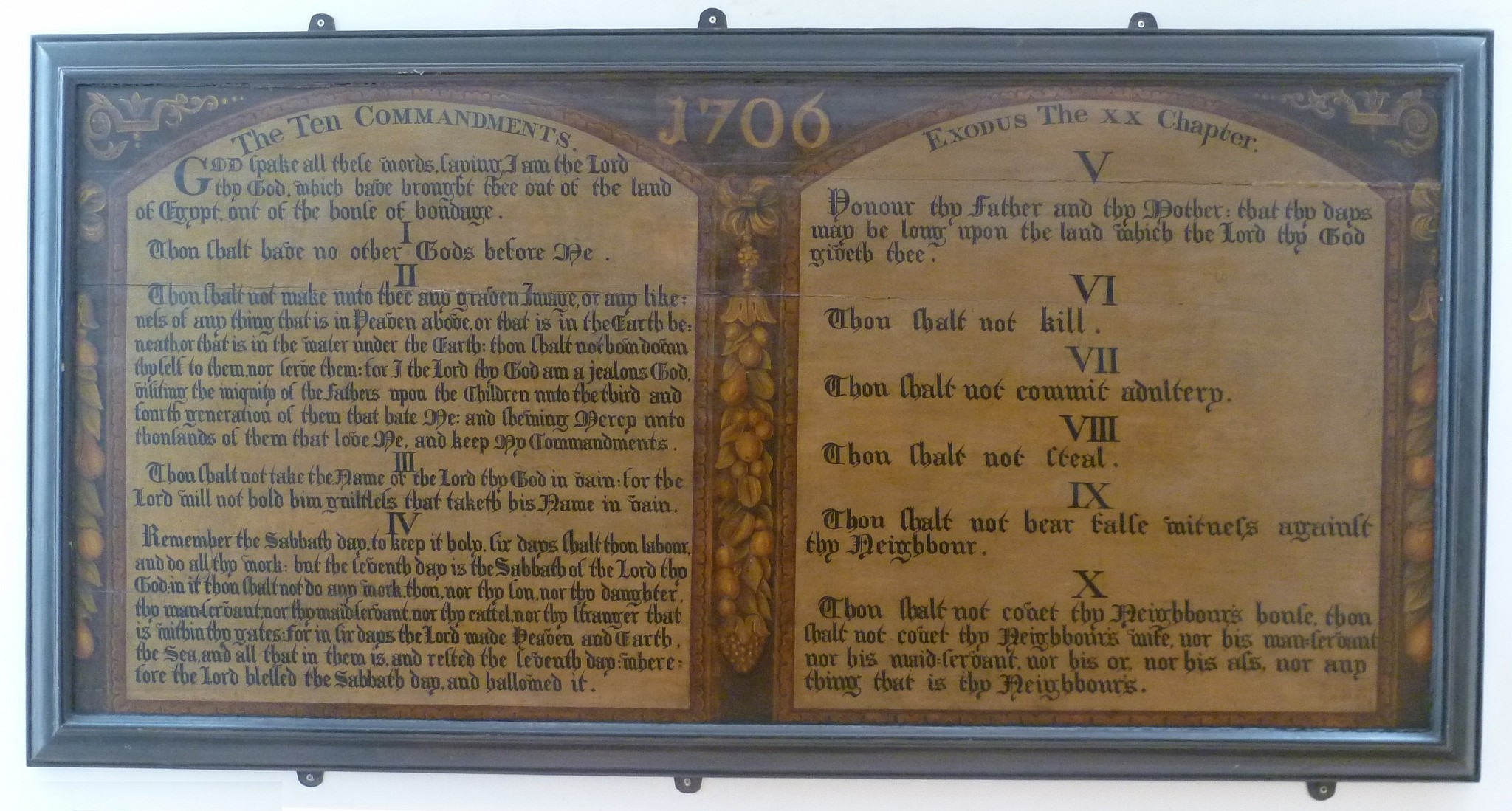

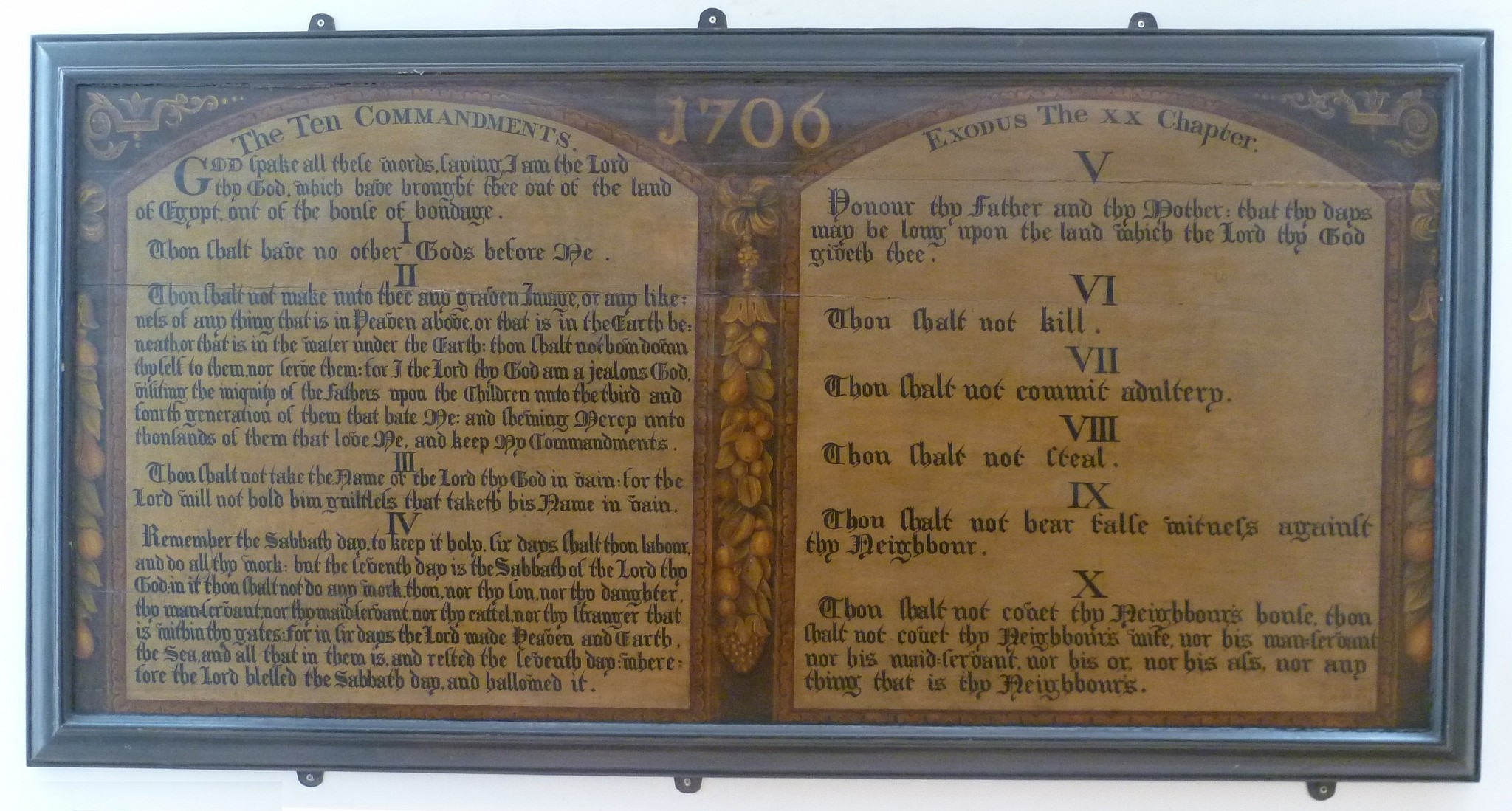

This foundation of the Roman legal system was compiled some 900 years after the Ten Commandments were given to the Israelites, according to the Torah’s chronology. But some 600-900 years before our record of how the Rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud viewed the Ten Commandments and their place in the Jewish legal system.

In contrast with the Twelve Tables, which were placed publicly in the Forum for all to see, the two tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments were sealed in the Ark of the Covenant, which was never opened. The Ark itself was hidden away in the holiest part of the Tabernacle (and later the Temple) and only seen on one day of the year by only one person (the High Priest). In the Second Temple era the Ark was no longer there, having been either placed in a hidden and forgotten chamber deep within the Temple,or taken to Ethiopia by Solomon’s son.

The Twelve Tables came at the insistence of the people and were drawn up by a group of men. The Torah describes how the Ten Commandments were given by God and not only were they unasked for but according to rabbinic tradition the Israelites has to be forced to accept them.

The contrast between these two foundations of legal system is stark but the truth is that the prophets and rabbis removed virtually all meaning from the Ten Commandments.

Many of the prophets railed against the Jewish people for not observing the Torah and for not behaving correctly. None of them mentioned the Ten Commandments specifically in their criticisms of the people (though they did complain that the Jews were not keeping various commandments included in the Ten, along with other commandments that were not being kept).

Then the third century sage Rabbi Simlai stated (Makkot 23b) that the Israelites did not receive 10 commandments at Sinai but 613. (Medieval rabbis who listed the 613 all agreed that the number of Torah laws is actually far higher than that, and there are even more rabbinic laws). The Talmud (Makkot 24a) then lists other rabbis who seek out the most essential Commandments, reducing the list from 11 until eventually deciding on the single commandment of, “The righteous shall live by his faith,” (Habakkuk 2:4). None of the rabbis thought that the classic 10 were the most essential laws.

Not only did the rabbis ignore the Ten Commandments when listing the most essential laws but they also redefined them to remove their plain meaning. For example, “Do not steal,” (Exodus 20:12) is interpreted to mean “Do not kidnap” (Sanhedrin 86a). Theft is still biblically forbidden but is not one of the Ten.

Others, like the commandments to observe the Sabbath or honor one’s parents have become the subjects of vast collections of intricate laws which go well beyond (and sometimes contradict) the plain meaning of the words.

By the mishnaic period the Ten Commandments were reduced from a legal code to a prayer in the daily service (similar to the Shema). But then, in response to the rise of Christianity, the rabbis removed the Ten Commandments from prayer too (Berachot 12a).

So although representations of the Two Tablets appear in synagogues and court rooms, the Ten Commandments are virtually insignificant as a legal code.

Unlike the Roman tablets which are almost forgotten yet still impact our laws, the Ten Commandments are extremely well known, yet have very little influence on the Jewish legal system.

Until that time, laws had been a combination of whatever custom, tradition and the ruling judge (always a Patrician) decided. Nobody could even know if they were being treated fairly by the law because nobody knew exactly what the law was. Terentilius wanted the laws to be written down to give greater protection to all.

The Patricians eventually (in 450 BCE) agreed to the Plebian demands request. A group of 10 men, known as the Decemvirate were selected to draw up the laws. According to Livy the 10 men went first to Greece to study Athenian laws and those of other cities.

On their return the men of the Decemvirate drew up their laws, which were written on 12 bronze tables placed in the forum, so that they were accessible to all.

The tables themselves were destroyed and we only know some of what they contained from later sources. But we do know that they focused mainly on civil laws between private citizens, including land ownership rights, inheritance rights and damages. They also included some religious laws. The worst punishment (the death penalty) was reserved for those who corrupted the legal system — judges who took bribes and witnesses who gave false testimony.

Rome was not the first state to have written laws, but these tablets were influential for generations. They formed the basis of Roman law for centuries after and Roman students were taught to memorize them in school. In fact, these laws influenced the men who drafted the US Constitution and also form the basis of common law which is still part of our legal system today.

This foundation of the Roman legal system was compiled some 900 years after the Ten Commandments were given to the Israelites, according to the Torah’s chronology. But some 600-900 years before our record of how the Rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud viewed the Ten Commandments and their place in the Jewish legal system.

In contrast with the Twelve Tables, which were placed publicly in the Forum for all to see, the two tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments were sealed in the Ark of the Covenant, which was never opened. The Ark itself was hidden away in the holiest part of the Tabernacle (and later the Temple) and only seen on one day of the year by only one person (the High Priest). In the Second Temple era the Ark was no longer there, having been either placed in a hidden and forgotten chamber deep within the Temple,or taken to Ethiopia by Solomon’s son.

The Twelve Tables came at the insistence of the people and were drawn up by a group of men. The Torah describes how the Ten Commandments were given by God and not only were they unasked for but according to rabbinic tradition the Israelites has to be forced to accept them.

The contrast between these two foundations of legal system is stark but the truth is that the prophets and rabbis removed virtually all meaning from the Ten Commandments.

Many of the prophets railed against the Jewish people for not observing the Torah and for not behaving correctly. None of them mentioned the Ten Commandments specifically in their criticisms of the people (though they did complain that the Jews were not keeping various commandments included in the Ten, along with other commandments that were not being kept).

Then the third century sage Rabbi Simlai stated (Makkot 23b) that the Israelites did not receive 10 commandments at Sinai but 613. (Medieval rabbis who listed the 613 all agreed that the number of Torah laws is actually far higher than that, and there are even more rabbinic laws). The Talmud (Makkot 24a) then lists other rabbis who seek out the most essential Commandments, reducing the list from 11 until eventually deciding on the single commandment of, “The righteous shall live by his faith,” (Habakkuk 2:4). None of the rabbis thought that the classic 10 were the most essential laws.

Not only did the rabbis ignore the Ten Commandments when listing the most essential laws but they also redefined them to remove their plain meaning. For example, “Do not steal,” (Exodus 20:12) is interpreted to mean “Do not kidnap” (Sanhedrin 86a). Theft is still biblically forbidden but is not one of the Ten.

Others, like the commandments to observe the Sabbath or honor one’s parents have become the subjects of vast collections of intricate laws which go well beyond (and sometimes contradict) the plain meaning of the words.

By the mishnaic period the Ten Commandments were reduced from a legal code to a prayer in the daily service (similar to the Shema). But then, in response to the rise of Christianity, the rabbis removed the Ten Commandments from prayer too (Berachot 12a).

So although representations of the Two Tablets appear in synagogues and court rooms, the Ten Commandments are virtually insignificant as a legal code.

Unlike the Roman tablets which are almost forgotten yet still impact our laws, the Ten Commandments are extremely well known, yet have very little influence on the Jewish legal system.

Wednesday, January 16, 2019

Parshat Beshalach: The Green Book

The “Green Book” won several awards at the Golden Globes last week, including “Best Motion Picture.” The movie, set in 1960, tells the story of the relationship between an African-American classical pianist and the Italian-American bouncer he hires to drive him on a concert tour through the racially divided deep south.

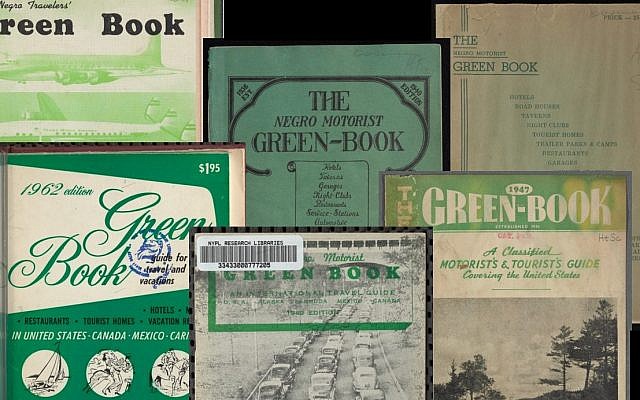

The movie’s title comes from an annual directory published by and named for Victor Hugo Green which listed hotels, stores and gas stations that welcomed African Americans. The full title of the directory was “The Negro Motorist Green Book” and it was published every year from 1936-1966. The guide, which was almost forgotten over the decades, was essential in the era of racial segregation, enforced by legislation known as the Jim Crow laws.

These laws, upheld by the Supreme Court, maintained racial segregation in all public facilities in the southern states of the US. The court ruled that Jim Crow did not violate the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution — which ensured equal protection” to all people — by invoking the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made racial discrimination illegal, but until that time the Green Book was a valuable guide for African-American motorists at a time when the relative low cost of motoring meant that many Americans took to the roads, especially those looking to escape the racism and segregation they experienced on public transport.

However, driving across America was not easy for people of color when many gas stations, hostels, restaurants and stores refused to serve them. Even finding a public bathroom was sometimes difficult. Many African-American travelers were forced to pack not only food for their journey, but also carry spare fuel and sometimes even a portable toilet. And if the car broke down, it was sometimes almost impossible to find a mechanic who would fix it for them. There were also thousands of so-called “sundown towns,” which barred non-whites after dark (one of which features in the movie).

This was why Green’s guide became invaluable. In the introduction to the 1949 edition he wrote, “With the introduction of this travel guide in 1936, it has been our idea to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.”

Green was a postal worker from Harlem, New York, and he published 15,000 copies of his guide each year. He said the inspiration for his guide came from similar Jewish publications.

The Jewish press has long published information about places that are restricted and there are numerous publications that give the gentile whites all kinds of information.

Jews continued to face discrimination when Green launched his guide, though the peak of anti-Semitism in the US was in the 1920s. That decade may have heralded in the age of motoring, but the American father of the motorcar, Henry Ford, was an avowed anti-Semite who blamed the Jews for World War I (and for almost everything else). In 1924, the government passed the Johnson–Reed Act, effectively severely limiting immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe. The Ku Klux Klan, newly reformed in 1915, claimed 4-5 million members by the 1920s. Hatred of Jews in America was widespread.

In response, Jews created their own philanthropic societies, their own hotels and resorts, their own lobbying groups, and their own guides to where Jews were welcomed. By the 1960s, Jews were at the forefront in the fight against discrimination of all kinds, and were among the founders and early funders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

According to a PBS show, Jews were at the heart of the fight against Jim Crow.

The American Jewish Committee, the American Jewish Congress, and the Anti-Defamation League were central to the campaign against racial prejudice. Jews made substantial financial contributions to many civil rights organizations, including the NAACP, the Urban League, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. About 50 percent of the civil rights attorneys in the South during the 1960s were Jews, as were over 50 percent of the Whites who went to Mississippi in 1964 to challenge Jim Crow Laws.

Jews knew that those who discriminated against minorities were the same people who hated Jews. The Jews of American felt that standing up for minorities was not only the right thing to do morally, but also the best way of combatting anti-Semitism.

The truth is, however, that anti-Semitism, the hatred of Jews, began millennia ago, in an incident we read in this week’s Torah portion.

After the Israelites miraculously left Egypt, everyone thought they were invincible. The Torah describes how they split the Red Sea, defeated Pharaoh’s army, and were guided by a column of fire and a pillar of smoke. Nobody in their right mind would have challenged the Israelites at the peak of their power.

Yet along came the tribe of Amalek and attacked the people, as they wandered through the desert. “And Amalek came and warred with Israel in Rephidim” (Exodus 17:8).

Amalek was not threatened by the Jews, who were heading to the Land of Canaan. The Jews had no resources that Amalek wanted or needed. How did their leader inspire the Amalekites to fight what must have seemed a suicidal war? Did he encourage them to fight by claiming that the Israelites were “criminals, drug dealers, and rapists” (or whatever was the equivalent at that time)? What other methods did he use to get his supporters to destroy themselves in order to get rid of the Israelites?

Amalek fought against the Israelites for no reason other than a hatred of Jews. Their war with Israel was the precursor to an eternal war against the Jews fought by those who hate Jews, as the verse states (Exodus 17:16):

He said, ‘For his hand is on the throne of God, there is a war between God and Amalek from generation to generation.’

Amalek was one single tribe that were wiped out thousands of years ago. But Amalek’s spiritual heirs, who continue to hate the Jews, remain strong to this day.

In 1948, Green wrote, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

Things have improved in so many ways in the US for minorities, but there is still a long way to go. Though discrimination based on race is now illegal, hatred of minorities is still widespread on social media and political rhetoric. The Green Book is no longer published and is almost forgotten. But the hatred of those who are different in the color of their skin, their religion or their ethnicity remains strong in some circles.

The last line of the introduction in the 1937 edition of the Green Book states, “Let’s all get together and make motoring better.” This message is equally relevant now, though I would alter it to read, “Let’s all get together to make the entire world better.”

—

With thanks to the wonderful podcast 99% Invisible for the inspiration behind this d’var Torah.

The movie’s title comes from an annual directory published by and named for Victor Hugo Green which listed hotels, stores and gas stations that welcomed African Americans. The full title of the directory was “The Negro Motorist Green Book” and it was published every year from 1936-1966. The guide, which was almost forgotten over the decades, was essential in the era of racial segregation, enforced by legislation known as the Jim Crow laws.

These laws, upheld by the Supreme Court, maintained racial segregation in all public facilities in the southern states of the US. The court ruled that Jim Crow did not violate the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution — which ensured equal protection” to all people — by invoking the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made racial discrimination illegal, but until that time the Green Book was a valuable guide for African-American motorists at a time when the relative low cost of motoring meant that many Americans took to the roads, especially those looking to escape the racism and segregation they experienced on public transport.

However, driving across America was not easy for people of color when many gas stations, hostels, restaurants and stores refused to serve them. Even finding a public bathroom was sometimes difficult. Many African-American travelers were forced to pack not only food for their journey, but also carry spare fuel and sometimes even a portable toilet. And if the car broke down, it was sometimes almost impossible to find a mechanic who would fix it for them. There were also thousands of so-called “sundown towns,” which barred non-whites after dark (one of which features in the movie).

This was why Green’s guide became invaluable. In the introduction to the 1949 edition he wrote, “With the introduction of this travel guide in 1936, it has been our idea to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.”

Green was a postal worker from Harlem, New York, and he published 15,000 copies of his guide each year. He said the inspiration for his guide came from similar Jewish publications.

The Jewish press has long published information about places that are restricted and there are numerous publications that give the gentile whites all kinds of information.

Jews continued to face discrimination when Green launched his guide, though the peak of anti-Semitism in the US was in the 1920s. That decade may have heralded in the age of motoring, but the American father of the motorcar, Henry Ford, was an avowed anti-Semite who blamed the Jews for World War I (and for almost everything else). In 1924, the government passed the Johnson–Reed Act, effectively severely limiting immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe. The Ku Klux Klan, newly reformed in 1915, claimed 4-5 million members by the 1920s. Hatred of Jews in America was widespread.

In response, Jews created their own philanthropic societies, their own hotels and resorts, their own lobbying groups, and their own guides to where Jews were welcomed. By the 1960s, Jews were at the forefront in the fight against discrimination of all kinds, and were among the founders and early funders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

According to a PBS show, Jews were at the heart of the fight against Jim Crow.

The American Jewish Committee, the American Jewish Congress, and the Anti-Defamation League were central to the campaign against racial prejudice. Jews made substantial financial contributions to many civil rights organizations, including the NAACP, the Urban League, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. About 50 percent of the civil rights attorneys in the South during the 1960s were Jews, as were over 50 percent of the Whites who went to Mississippi in 1964 to challenge Jim Crow Laws.

Jews knew that those who discriminated against minorities were the same people who hated Jews. The Jews of American felt that standing up for minorities was not only the right thing to do morally, but also the best way of combatting anti-Semitism.

The truth is, however, that anti-Semitism, the hatred of Jews, began millennia ago, in an incident we read in this week’s Torah portion.

After the Israelites miraculously left Egypt, everyone thought they were invincible. The Torah describes how they split the Red Sea, defeated Pharaoh’s army, and were guided by a column of fire and a pillar of smoke. Nobody in their right mind would have challenged the Israelites at the peak of their power.

Yet along came the tribe of Amalek and attacked the people, as they wandered through the desert. “And Amalek came and warred with Israel in Rephidim” (Exodus 17:8).

Amalek was not threatened by the Jews, who were heading to the Land of Canaan. The Jews had no resources that Amalek wanted or needed. How did their leader inspire the Amalekites to fight what must have seemed a suicidal war? Did he encourage them to fight by claiming that the Israelites were “criminals, drug dealers, and rapists” (or whatever was the equivalent at that time)? What other methods did he use to get his supporters to destroy themselves in order to get rid of the Israelites?

Amalek fought against the Israelites for no reason other than a hatred of Jews. Their war with Israel was the precursor to an eternal war against the Jews fought by those who hate Jews, as the verse states (Exodus 17:16):

He said, ‘For his hand is on the throne of God, there is a war between God and Amalek from generation to generation.’

Amalek was one single tribe that were wiped out thousands of years ago. But Amalek’s spiritual heirs, who continue to hate the Jews, remain strong to this day.

In 1948, Green wrote, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

Things have improved in so many ways in the US for minorities, but there is still a long way to go. Though discrimination based on race is now illegal, hatred of minorities is still widespread on social media and political rhetoric. The Green Book is no longer published and is almost forgotten. But the hatred of those who are different in the color of their skin, their religion or their ethnicity remains strong in some circles.

The last line of the introduction in the 1937 edition of the Green Book states, “Let’s all get together and make motoring better.” This message is equally relevant now, though I would alter it to read, “Let’s all get together to make the entire world better.”

—

With thanks to the wonderful podcast 99% Invisible for the inspiration behind this d’var Torah.

Thursday, January 10, 2019

Parshat Bo: The power of youth

For more than a hundred years, from the end of the fifth century BCE, the Spartan army was the supreme fighting force in the ancient world.

The Spartans were not known for their advances in science, technology or medicine. Apart from the Chilon in the 6th century BCE (who was renowned as one of the Seven Sages of Greece), Sparta produced no philosophers. But in the field of war they excelled more than anyone else. The culture of Sparta was totally focused on military training and creating the best fighting force in the world.

Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War I:10) referred to the Sparta by its ancient name of Ladaeaemon when he wrote:

From the age of 7, Spartan boys would leave their homes and enter the agoge system where they were beaten, starved and often died, but where they were trained in the art of war. At the age of 20 they would enter the military, where they would continue to serve until they reached the age of 60. Unusually for the ancient world, girls also received an education, and were comparatively well cared for, so that they could give birth to and raise the finest soldiers. Spartan women lived longer than their counterparts in other Greek cities, most likely because they were well fed and in better health.

Everything in Spartan society was focused on having the finest army and encouraging the best fighters. When Spartans died, only soldiers who had died in battle or women who died in childbirth were entitled to have marked headstones.

Although life was extremely tough for boys between the ages of seven and 20, it was even more dangerous for Spartan babies. Shortly after birth, a mother would bathe her child in wine to see if he was strong. If he survived, he was brought by his father to the Gerousia, the council of elders, who decided whether the baby was fit enough to be raised. Any child considered deformed or puny was thrown to its death into a chasm on Mount Taygetos known as Ceadas (interestingly, the modern name for Taygetos is Mount Profitis Ilias, named for the prophet Elijah). Some modern scholars argue that babies were not thrown into the chasm but were instead left to die on the mountainside.

For the Spartans, children had no intrinsic value in their own right. They became honorable and important only once they reached adulthood and were able to fight.

In this week’s Torah reading, Pharaoh challenges Moses about the role of children in religious, communal life.

Even though Moses was planning on leading the Israelites out of Egypt for good, he told Pharaoh they wanted to go to the desert to celebrate a festival. Rabbenu Bahya explains that Moses was alluding to the festival of Shavuot, when the Israelites stood at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah.

Pharaoh, convinced by his servants that he had no option but to allow the Jews to leave, told Moses and Aharon, “Go worship the Lord, your God. Who are those who are going?” (Exodus 10:8).

Moses replied:

Pharaoh scoffed at the idea of allowing the children to go to worship God at a festival. “So be it, may God be with you, when I will send you and your children,” he said. “Look that evil lies before you. Not so. Please go the men and worship God, for that is what you are requesting” (Exodus 10:10-11).

At the simplest level, the verse shows that Pharaoh was afraid the Israelites would leave and never return. So he insisted on keeping the children as hostages.

However, Ramban explains in his commentary, that the argument between them was about the role of children in rituals and religion. Moses said that even the children had to take part in the festival, whereas Pharaoh said that worship was only for adults and not for children.

In Pharaoh’s defense, when the children of Jacob left Egypt to bury their father in Israel — which was itself a kind of ritual — they left their young behind in Egypt (Genesis 50:7-8).

But perhaps Pharaoh shared the world view of the Spartans — that children had no intrinsic value. And perhaps he went a step further in saying that they had no part to play in worshiping God.

Yet at Mount Sinai it was specifically the children who offered the sacrifices, not the adults. “And he sent the youths of the Children of Israel and they offered offerings and sacrifices peace sacrifices to God, of bulls” (Exodus 24:5).

The idea that the children would offer sacrifices remained shocking to the Greek world even hundreds of years after Moses and the Spartans. The Talmud (Megillah 9a) relates that when Ptolemy ordered the rabbis to translate the Torah into Greek, one of the alterations they made was to change the phrase from “sent the youths” to “sent the elect” so as not to offend the Greeks or lead them to disparage Judaism.

It is fundamental to Judaism that children are included in the rituals and worship. The Torah stresses that once every seven years all the Jews must gather in Jerusalem: “The men, the women the children and the converts, in order that they may hear and in order that they may learn, and fear the Lord, your God, and observe and do all the words of this Torah,” (Deuteronomy 31:12).

This is the message that Moses delivered to Pharaoh shortly before leading the Israelites to their freedom.

Cross posted from Times of Israel.

The Spartans were not known for their advances in science, technology or medicine. Apart from the Chilon in the 6th century BCE (who was renowned as one of the Seven Sages of Greece), Sparta produced no philosophers. But in the field of war they excelled more than anyone else. The culture of Sparta was totally focused on military training and creating the best fighting force in the world.

Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War I:10) referred to the Sparta by its ancient name of Ladaeaemon when he wrote:

For I suppose if Lacedaemon were to become desolate, and the temples and the foundations of the public buildings were left, that as time went on there would be a strong disposition with posterity to refuse to accept her fame as a true exponent of her power. And yet they occupy two-fifths of Peloponnese and lead the whole, not to speak of their numerous allies without.

From the age of 7, Spartan boys would leave their homes and enter the agoge system where they were beaten, starved and often died, but where they were trained in the art of war. At the age of 20 they would enter the military, where they would continue to serve until they reached the age of 60. Unusually for the ancient world, girls also received an education, and were comparatively well cared for, so that they could give birth to and raise the finest soldiers. Spartan women lived longer than their counterparts in other Greek cities, most likely because they were well fed and in better health.

Everything in Spartan society was focused on having the finest army and encouraging the best fighters. When Spartans died, only soldiers who had died in battle or women who died in childbirth were entitled to have marked headstones.

Although life was extremely tough for boys between the ages of seven and 20, it was even more dangerous for Spartan babies. Shortly after birth, a mother would bathe her child in wine to see if he was strong. If he survived, he was brought by his father to the Gerousia, the council of elders, who decided whether the baby was fit enough to be raised. Any child considered deformed or puny was thrown to its death into a chasm on Mount Taygetos known as Ceadas (interestingly, the modern name for Taygetos is Mount Profitis Ilias, named for the prophet Elijah). Some modern scholars argue that babies were not thrown into the chasm but were instead left to die on the mountainside.

For the Spartans, children had no intrinsic value in their own right. They became honorable and important only once they reached adulthood and were able to fight.

In this week’s Torah reading, Pharaoh challenges Moses about the role of children in religious, communal life.

Even though Moses was planning on leading the Israelites out of Egypt for good, he told Pharaoh they wanted to go to the desert to celebrate a festival. Rabbenu Bahya explains that Moses was alluding to the festival of Shavuot, when the Israelites stood at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah.

Pharaoh, convinced by his servants that he had no option but to allow the Jews to leave, told Moses and Aharon, “Go worship the Lord, your God. Who are those who are going?” (Exodus 10:8).

Moses replied:

With our youths and our elderly we shall go; with our sons and our daughters, with our flocks and our herds we shall go, for it is a festival of God for us. (Exodus 10:9)

Pharaoh scoffed at the idea of allowing the children to go to worship God at a festival. “So be it, may God be with you, when I will send you and your children,” he said. “Look that evil lies before you. Not so. Please go the men and worship God, for that is what you are requesting” (Exodus 10:10-11).

At the simplest level, the verse shows that Pharaoh was afraid the Israelites would leave and never return. So he insisted on keeping the children as hostages.

However, Ramban explains in his commentary, that the argument between them was about the role of children in rituals and religion. Moses said that even the children had to take part in the festival, whereas Pharaoh said that worship was only for adults and not for children.

In Pharaoh’s defense, when the children of Jacob left Egypt to bury their father in Israel — which was itself a kind of ritual — they left their young behind in Egypt (Genesis 50:7-8).

And Joseph went up to bury his father, and with him went up all Pharaoh’s servants the elders of his house and all the elders of Egypt. And all the house of Joseph and his brothers and his father’s house. Only their children, their flocks and their sheep they left in the land of Goshen.

But perhaps Pharaoh shared the world view of the Spartans — that children had no intrinsic value. And perhaps he went a step further in saying that they had no part to play in worshiping God.

Yet at Mount Sinai it was specifically the children who offered the sacrifices, not the adults. “And he sent the youths of the Children of Israel and they offered offerings and sacrifices peace sacrifices to God, of bulls” (Exodus 24:5).

The idea that the children would offer sacrifices remained shocking to the Greek world even hundreds of years after Moses and the Spartans. The Talmud (Megillah 9a) relates that when Ptolemy ordered the rabbis to translate the Torah into Greek, one of the alterations they made was to change the phrase from “sent the youths” to “sent the elect” so as not to offend the Greeks or lead them to disparage Judaism.

It is fundamental to Judaism that children are included in the rituals and worship. The Torah stresses that once every seven years all the Jews must gather in Jerusalem: “The men, the women the children and the converts, in order that they may hear and in order that they may learn, and fear the Lord, your God, and observe and do all the words of this Torah,” (Deuteronomy 31:12).

This is the message that Moses delivered to Pharaoh shortly before leading the Israelites to their freedom.

Cross posted from Times of Israel.

Wednesday, January 02, 2019

Parshat Vaera: The Power of Two

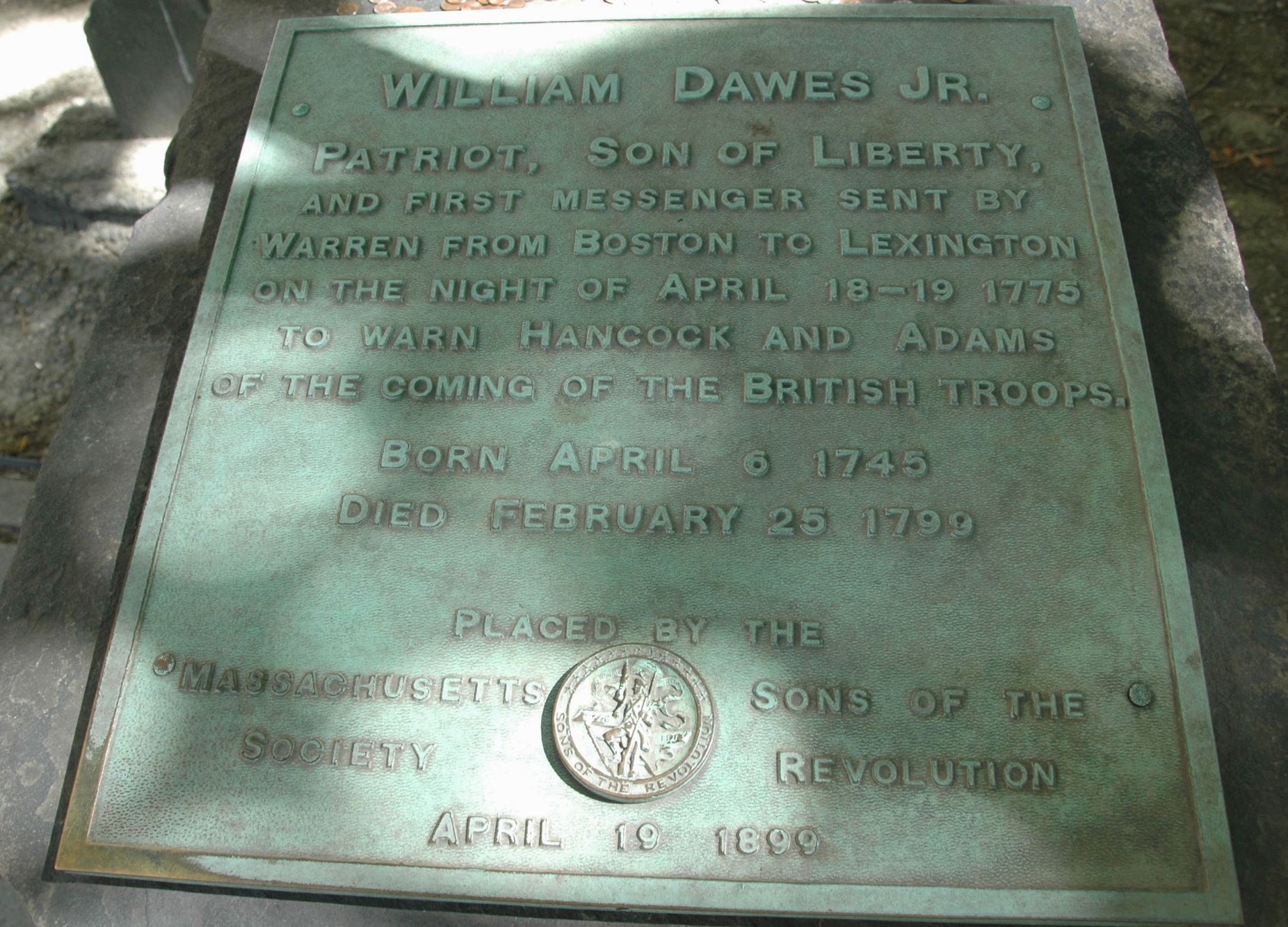

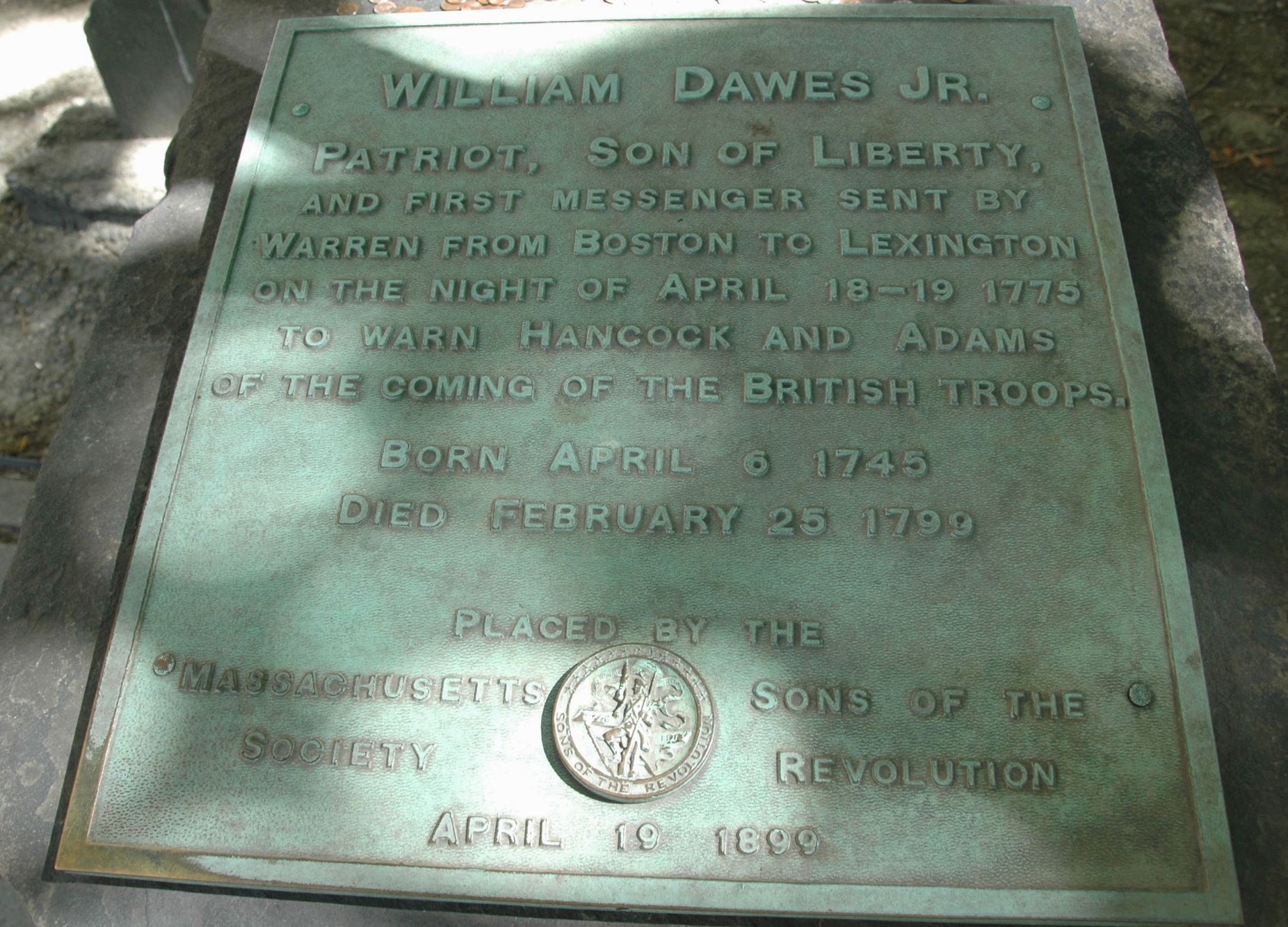

Even non-Americans like me have heard of Paul Revere and his famous midnight ride during the American Revolution, even if they don’t know the actual meaning of Longfellow’s famous line, “One if by land, and two if by sea.” But far fewer people have ever heard of William Dawes, who made the same midnight ride, and was even more audacious than Revere in getting past the British.

In fact, I suspect that the only place people may have heard of Dawes is in “The Tipping Point,” where Malcolm Gladwell contrasts his failure with Revere’s success.

Gladwell uses Revere as a paradigm of a “connector” who can take an idea and turn it into an epidemic. He writes:

“When he died, his funeral was attended, in the words of one contemporary newspaper account, by ‘troops of people.’ He was a fisherman and a hunter, a cardplayer and a theater-lover, a frequenter of pubs and a successful businessman. He was active in the local Masonic Lodge and was a member of several select social clubs. He was also a doer, a man blessed — as David Hackett Fischer recounts in his brilliant book Paul Revere’s Ride — with an ‘uncanny genius for being at the center of events.’”

In contrast, nobody is certain what happened to Dawes after his midnight ride. Adding insult to injury, in 2007, it was discovered that he may not even be buried in his marked grave in Boston’s King’s Chapel Burying Ground, but may actually be buried five miles away with his wife.

Yet he was as much a patriot as Revere and played an equally important role in the revolutionary war.

While Revere was a silversmith, Dawes was a tanner. Both would have had a large number of contacts and connections. Dawes was so dedicated to independence that he boycotted British goods — the Boston Gazette stated that at his wedding, he wore a suit made entirely in America.

Like Revere and Dr Joseph Warren, who sent both messengers, Dawes was a Freemason. He had built up a large network of military connections. In October 1774, he led a group who brazenly stole two cannons from a British arsenal while the British soldiers were out at roll call. He often went out recruiting supporters for the colonial cause, sometimes taking his granddaughter with him, so that the British would not suspect he was up to anything untoward.

On the night of April 18, 1775, while Revere rowed across the Charles River in a boat, the 30-year-old Dawes was charged by Warren on the more dangerous overland route from Boston to Lexington to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams of the impending British invasion. His path required him to pass through a British-guarded checkpoint at Boston neck. Nobody knows for certain how he managed to get past the sentries, but it is likely that he had cultivated friendships with them for some time, preparing for just such an eventuality.

So why is Revere so famous while Dawes has been so forgotten (or maligned on the rare occasion he is mentioned)?

It is true that Revere knocked on doors along his journey to Lexington, waking the revolutionary soldiers and preparing them for the invasion, whereas Dawes rode directly to Hancock and Adams without stopping along the way (and, ironically, he was still beaten by Revere, who had a faster horse and a shorter route, and so was able to deliver the message before Dawes arrived). So, far fewer people were aware of Dawes’s daring ride.

But more likely Dawes was forgotten and Revere remembered due to the power of the written word. Dawes did not leave a record of his heroism, whereas Revere wrote three accounts of his ride, the last written 23 years after the event in a letter to Jeremy Belknap, Secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

And probably the most important reason that Dawes was forgotten by history is due to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s historically inaccurate poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Gladwell praises Revere and derides Dawes, writing: “This chapter is about the people critical to social epidemics and what makes someone like Paul Revere different from someone like William Dawes.” But one could equally argue that Revere’s fame was not because he was a better connector than Dawes, but simply because he got better coverage after the fact.

In contrast to the famous Revere and the forgotten Dawes, the Torah goes to great lengths to stress that the two revolutionary leaders who took the Israelites out of Egypt had different roles, yet were equals.

Moses was the chosen leader, but it was Aaron who was the social “connector” who could speak to both the downtrodden slaves and to Pharaoh. Moses was raised in Pharaoh’s palace, then fled the country, only to return decades later, at God’s command. In contrast, Aaron spent his entire life strengthening bonds between himself and others. Whereas Moses represented strict application of the law, described as “Let the judgment pierce the mountain,” (Midrash Shochar Tov on Psalms 90), Aaron embodied, “Love peace and pursue peace, love people and bring them close to Torah,” (Pirkei Avot 1:12).

Moses acknowledged his own shortcomings and God informed him that he could only succeed alongside his brother (Exodus 6:12-13).

In the following chapter (Exodus 7:1-2) the Torah makes it even more clear that their mission could only succeed with Aaron being the one to spread the word.

At some point, Moses found his voice and was able to speak directly to Pharaoh, and later on was also able to speak to the fledgling Jewish nation, becoming the law-bearer who informed them of all God’s decisions. And Aaron became an important figure in his own right, as the High Priest, such that he and his descendants had the task of acting as intermediaries between God and the Jewish people in the Temple rituals. The Torah stresses (Exodus 6:26-27) that both brothers were equally important, referring to them as a single person and switching the order of their names to show their co-leadership.

But at the outset of their revolution, neither could have done it without the other.

In fact, I suspect that the only place people may have heard of Dawes is in “The Tipping Point,” where Malcolm Gladwell contrasts his failure with Revere’s success.

Gladwell uses Revere as a paradigm of a “connector” who can take an idea and turn it into an epidemic. He writes:

“When he died, his funeral was attended, in the words of one contemporary newspaper account, by ‘troops of people.’ He was a fisherman and a hunter, a cardplayer and a theater-lover, a frequenter of pubs and a successful businessman. He was active in the local Masonic Lodge and was a member of several select social clubs. He was also a doer, a man blessed — as David Hackett Fischer recounts in his brilliant book Paul Revere’s Ride — with an ‘uncanny genius for being at the center of events.’”

In contrast, nobody is certain what happened to Dawes after his midnight ride. Adding insult to injury, in 2007, it was discovered that he may not even be buried in his marked grave in Boston’s King’s Chapel Burying Ground, but may actually be buried five miles away with his wife.

Yet he was as much a patriot as Revere and played an equally important role in the revolutionary war.

While Revere was a silversmith, Dawes was a tanner. Both would have had a large number of contacts and connections. Dawes was so dedicated to independence that he boycotted British goods — the Boston Gazette stated that at his wedding, he wore a suit made entirely in America.

Like Revere and Dr Joseph Warren, who sent both messengers, Dawes was a Freemason. He had built up a large network of military connections. In October 1774, he led a group who brazenly stole two cannons from a British arsenal while the British soldiers were out at roll call. He often went out recruiting supporters for the colonial cause, sometimes taking his granddaughter with him, so that the British would not suspect he was up to anything untoward.

On the night of April 18, 1775, while Revere rowed across the Charles River in a boat, the 30-year-old Dawes was charged by Warren on the more dangerous overland route from Boston to Lexington to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams of the impending British invasion. His path required him to pass through a British-guarded checkpoint at Boston neck. Nobody knows for certain how he managed to get past the sentries, but it is likely that he had cultivated friendships with them for some time, preparing for just such an eventuality.

So why is Revere so famous while Dawes has been so forgotten (or maligned on the rare occasion he is mentioned)?

It is true that Revere knocked on doors along his journey to Lexington, waking the revolutionary soldiers and preparing them for the invasion, whereas Dawes rode directly to Hancock and Adams without stopping along the way (and, ironically, he was still beaten by Revere, who had a faster horse and a shorter route, and so was able to deliver the message before Dawes arrived). So, far fewer people were aware of Dawes’s daring ride.

But more likely Dawes was forgotten and Revere remembered due to the power of the written word. Dawes did not leave a record of his heroism, whereas Revere wrote three accounts of his ride, the last written 23 years after the event in a letter to Jeremy Belknap, Secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

And probably the most important reason that Dawes was forgotten by history is due to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s historically inaccurate poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Gladwell praises Revere and derides Dawes, writing: “This chapter is about the people critical to social epidemics and what makes someone like Paul Revere different from someone like William Dawes.” But one could equally argue that Revere’s fame was not because he was a better connector than Dawes, but simply because he got better coverage after the fact.

In contrast to the famous Revere and the forgotten Dawes, the Torah goes to great lengths to stress that the two revolutionary leaders who took the Israelites out of Egypt had different roles, yet were equals.