One dark Chicago night in 1926, Fats Waller was leaving his regular gig at the Sherman Hotel when he was surrounded by four armed men. Waller was one of the most popular jazz musicians of his time, and one of the most prolific composers. But he had no idea what was about to happen.

One of the armed men shoved a pistol into Waller’s ample belly and told him to get into the limo. Fearing for his life, the pianist did as he was told. He was driven out of town, down to Cicero. The car pulled up outside the Hawthorn Inn and Waller was led inside, gun still pointed at his back, and told to sit down at the piano and start playing.

As he looked around him, Waller realized that he was at a birthday party for the infamous Al Capone, who had relocated his headquarters to Cicero, where he had a better deal with officials, police, and rival gangs than he had had in Chicago. Capone was turning 27 and Fats Waller was a surprise birthday present from “the boys.”

In 1926, America was in the grip of prohibition, and as a result, Capone was at the height of his power. It was still three years before the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, after which he was dubbed “Public Enemy Number One.” It was five years before Capone was sent to jail for tax evasion, where he would serve eight years of an 11-year sentence, including time in Alcatraz, and just over six years after that, aged 48, Capone would be dead.

Al Capone, after his arrest in 1930 on vagrancy charges. (Public Domain, Chicago Bureau of the FBI/ Wikimedia Commons)

But 1926 was a great time to be alive. Capone was head of a massive crime organization following the “resignation” of Johnny Torrio, who had been shot several times. The Chicago Outfit ran an illegal brewery and transportation network that reached across the border to Canada. Several establishments that refused to buy their alcohol from the Outfit were mysteriously blown up, leading to an estimated 100 deaths.

Ironically, though several of Al’s brothers worked with him in the alcohol business, his older brother Vincenzo Capone changed his name to Richard James Hart and became a prohibition agent in Homer, Nebraska. There, he orchestrated a series of successful raids against bootleggers, which earned him the nickname “Two-gun” Hart.

Capone’s reign as head of the crime gang also saw an increase in the number of brothels in Chicago. Yet despite his ruthless violence against rivals and others, Capone gave large donations to charity and earned a reputation as a modern-day Robin Hood.

In addition to a penchant for the ladies, Capone liked wearing fancy suits, and enjoyed expensive cigars, gourmet food and drink. He was also known for wearing flashy and flamboyant jewelry. And he loved to party.

So, when his henchmen were trying to come up with a present to give their boss for his 27th birthday, they could think of nothing better than bringing him Fats Waller, one of his favorite musicians.

Waller played at gunpoint for three days, entertaining the mafia boss and those who were celebrating with him. But the pianist loved to party almost as much as Capone did, especially as after every song he received large cash tips and drinks. By the time he stumbled out of the Hawthorn Inn, Waller had thousands of dollars in his pockets and had developed a taste for fine champagne.

He also had a watertight excuse if he were ever questioned by the FBI — he could honestly claim he had no ties to the mob boss. Waller never played for Capone again, but continued touring until 1943, when he died of pneumonia, aged only 39. At his funeral, the pastor who eulogized him praised Waller, saying he “always played to a packed house.”

The story of Capone and the kidnapped musician got me thinking about how difficult birthdays are. Not only is it hard to find the right present for someone (after all, not everyone can have Fats Waller at gunpoint), but also how tricky it is to actually keep track of birthdays.

The earliest recorded birthday was that of Pharaoh, described in Genesis 40:20. As part of the celebrations, Pharaoh restored the chief butler to his position and executed the chief baker. However, it is possible that this was not actually the anniversary of Pharaoh’s birth, but rather the anniversary of his coronation. Many Pharaohs were believed to be deities once they ascended the throne, and thus it may mark his “rebirth” as a god.

The Palermo Stone in Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo. (G.dallorto/ Wikimedia Commons)

We know from the Palermo Stone that the ancient Pharaohs celebrated a feast called “Appearance of the King” every two years, on the anniversary of their coronation. Is it possible that this is what Pharaoh was celebrating? Perhaps that explained the strange Hebrew phrase “yom huledet et par’o” rather than the simpler “yom huledet par’o” that we would use in modern Hebrew.

You see, until recently it was rather difficult to know when someone’s birthday was. Until modern record keeping, most people didn’t know the day they were born. A friend of mine, who came to Israel with his parents from Morocco as a child, recently turned 70. But nobody knows exactly when. When his mother and father arrived in Israel, they did not know his date of birth. In Morocco, there were no birth certificates at that time. So the official documents list his birthday as 0/0/1949.

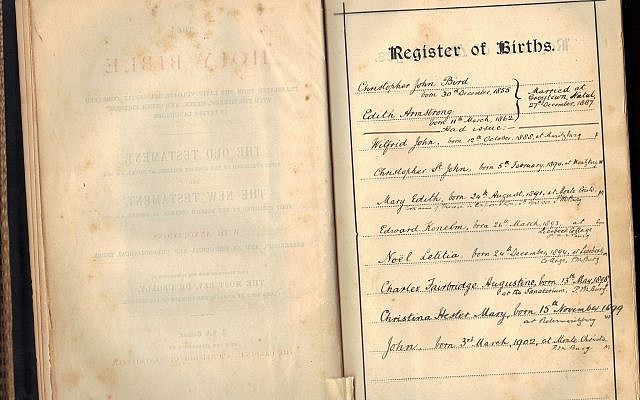

The modern practice of compulsory registration of births only started in the United Kingdom in about 1853. In the United States, it was only introduced in 1902. On September 2, 1990, the Convention on the Rights of the Child came into force. It was accepted by 191 countries, and gives children the right to a registered name and nationality at birth.

Bird family birth registry from Bird family bible. (CC BY-SA, Theobird/ Wikimedia Commons)

But before that records were kept sporadically. Some countries, even in ancient times, registered births for tax purposes. In some places, births were registered in local parishes or synagogues for religious reasons. Often, families would record births and deaths in prayer books or elsewhere. But there was no systematic documentation of a child’s date of birth.

It is possible that even in ancient times, parents looked at the stars when their child was born to know what his or her future had in store according to the astrologers. Thus, we find in the Talmud (Shabbat 156a) that one who is born under the sign of Mars will shed blood. So he will become a blood-letter, a thief, a ritual slaughterer, or a mohel (circumciser).

It is a much more difficult thing to pinpoint the exact date of a birth and know how to celebrate it a year later.

And knowing the length of a year is even more difficult. Nowadays, we celebrate secular birthdays and anniversaries according to the Gregorian calendar, which we note is (approximately) the time it takes for the earth to make one full orbit of the sun.

Earth orbiting the sun. (CC BY-SA, kristian fagerström/ Flickr)

But before the Israelites left Egypt, they were given a brand-new calendar — in fact the very first commandment they were given was to mark the first of Nisan as the beginning of the year. Of course, back then the month was not called Nisan — the names of the “Hebrew” months are Babylonian, and were introduced to the calendar during the Babylonian exile (see Ramban on Exodus 12:2). Before that, the months were called by the Torah “first month,” “second month,” “third month,” etc., although it seems from the book of I Kings (6:1 and 8:2) that they had other names too, such as “Ziv”’ and “Eitanim.”

But the new months they were given means that they now had a new way of calculating a year. It wasn’t the passage of the earth around the sun, but the completion of 12 (or sometimes 13) new moons.

Even if someone knew exactly on which day they were born, it is unlikely that they would also be able to calculate back to work out when their birthday fell according to this new calendar. For one thing, without seeing all the previous moons and without a Sanhedrin to declare the new month, it would have been impossible to know the length of any particular year.

So, although nowadays we take it for granted, it is worth noting that in this week’s Torah reading (Numbers 1:1-3), Moses, along with the leaders of each of the tribes, was instructed to count every man over the age of 20.

God spoke to Moses in the Sinai wilderness in the tent of meeting, on the first day of the second month in the second year after they left the land of Egypt, saying: Count the head of the entire congregation of the Children of Israel, according to their families and their father’s houses, by the number of names, a headcount of each male. From 20 years old and upward…

How would they know which of the men were 19 and a half and which were over the age of 20? They had just left years of slavery in Egypt and record-keeping was probably not high on their list of things to do.

We know that the tribe of Levi was counted from the age of 30 days. This solves the problem of record-keeping, but requires parents to note exactly the time of day the baby was born (because if the child was born after dark it would be already the next day, and if he was born during sunset, it is even more complicated). Also, it would have been unseemly for Moses and Aaron to enter the tents of women who had recently given birth. Therefore, several commentaries, including Kli Yakar and Ohr HaChaim, explain that Moses and Aaron would stand outside the tent and a heavenly voice would proclaim how many children over the age of 30 days were inside.

So, it is possible that miracles were also involved when they were counting all the men over the age of 20. Perhaps they had some sign by which they knew who had already had their respective birthdays and who was still a few days away.

Or perhaps they didn’t need to count precisely. Maybe anyone who was approximately 19 when they left Egypt was considered to be 20-years-old one year later.

Or maybe the confusion about birth dates explains the discrepancies in the number of men at the different times they were counted in the wilderness.

Birthdays are on my mind this week. I don’t think we should celebrate them in the same way that Pharaoh or Al Capone celebrated. But birthdays are a time to thank your parents for bringing you into existence. And they are also a good time for an annual stock-taking — while the earth has been traveling at about 107,000 kilometers per hour (67,000 miles per hour) around the sun, how far have we actually come as individuals?