Yet they knew they had a secret weapon. The crusaders knew there was a powerful Christian king living in the east, who at that very moment was leading a mighty army to save them. This king was named Prester John, but unfortunately he never came. Some said his army was unable to cross the Tigris river. Others said that it was not yet the time for him to come. And others said that Prester John was a myth and did not actually exist.

Stories of Prester John, also known as Presbyter John or John the Elder circulated throughout medieval European Christian.

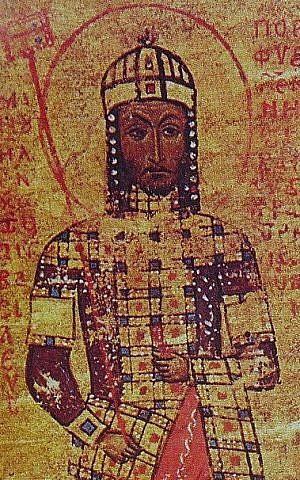

In 1165 a letter was received by Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus which was believed to be from the great king himself. The letter states that John, lives in the land beyond India, where, “Our land streams with honey and is overflowing with milk.” He is so powerful that he is served by 72 kings of the surrounding lands. He sent Manuel a fantastic description of his country:

“Our land is the home of elephants, dromedaries, camels, crocodiles, meta-collinarum, cametennus, tensevetes, wild asses, white and red lions, white bears, white merules, crickets, griffins, tigers, lamias, hyenas, wild horses, wild oxen, and wild men — men with horns, one-eyed men, men with eyes before and behind, centaurs, fauns, satyrs, pygmies, forty-ell high giants, cyclopses, and similar women. It is the home, too, of the phoenix and of nearly all living animals.”

Of course, the letter turned out to be a forgery, but nevertheless, a large part of the Christian world believed in this great king who would come to save them.

Even some Jews believed in Prester John. Joshua ben Joseph ibn Vives al-Lorqui (Joshua Lorki) was a 15th century Jewish doctor living in Alcañi, in Aragon, Spain. He served Benedict XIII and wrote a medical textbook in Arabic which was later translated into Hebrew as Gerem Hamaalot.

In a letter to Paul of Burgos (a Spanish Jew who converted to Christianity), Lorki wrote:

I know that it is certainly not hidden from you the matter well-known to us from stories of travelers who journeyed the length and breadth of the world, and also from letters of the Rambam, and we heard it from the traders from the ends of the earth… about those who dwell at the end of the earth in the land of Ethiopians, called Al-Chabash, and they made a deal with the Christian prince called Prester John…

By this time the legend of Prester John had him living in Africa. As the Indian subcontinent became more widely explored and better known, the Europeans realized that the great Christian King must reside in Ethiopia.

There were many attempts at forging ties between European countries and Ethiopia during the Middle Ages, and despite the denial of the Ethiopians, the Europeans continued to insist their King was Prester John.

Zara Yaqob was emperor of Ethopia from 1434 until his death in 1468. In 1441 he sent delegates to the Council of Florence where, despite their confusion and subsequent denials, the council prelates continued to refer to their monarch as Prester John (in Robert Silverberg’s “The Realm of Prester John”).

As late as 1751, the Czech missionary Remedius Prutky visited Ethiopia and asked Emperor Iyasu II about Prester John. He writes that Isayu was “astonished, and told me that the kings of Abyssinia had never been accustomed to call themselves by this name.”

Gradually the legend of Prester John died away but it continues to have an influence to this day. From Shakespeare’s Benedick, who offers Don Pedro to “…bring you the length of Prester John’s foot…” in “Much Ado About Nothing,” to appearances in issues of Marvel’s “Fantastic Four” and “Thor” to DC comics who featured him in “Arak: Son of Thunder” the legend lives on.

This was not the first time a nation waited for a powerful king from a distant land to come and save his people. It was not even the first time Ethiopia was the believed hidden refuge of a powerful king.

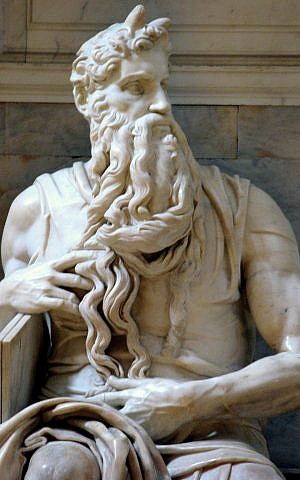

In this week’s Torah reading, Shemot, we are introduced to Moses who was saved from Pharaoh’s decree by Pharaoh’s daughter and raised in the royal palace. He was forced to flee after he killed an Egyptian who was persecuting an Israelite and was sentenced to death (Exodus 2:15). The same verse states that he went to Midian, where he eventually married Jethro’s daughter Zipporah.

We are not told how young Moses was when he fled Egypt, but he was 80 years old when he led the Jews out of Egypt. It seems that there are many decades unaccounted for by the Torah.

Although there is no mention of it in the Talmud or early Midrashim, several of the Torah commentaries say that Moses spent the intervening years ruling Ethiopia.

The verse states, “Miriam and Aaron spoke about Moses because of the Ethiopian woman he married, for he had married an Ethiopian woman,” (Numbers 12:1). Ibn Ezra and Rashbam, in their commentaries on that verse, explain that Moses married this wife while he was king of Ethiopia. Later commentaries including Sefer Hayashar, Menahem Azariah da Fano (Ma’amar Chikur Din 3:5) and Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain (Shem Mishmuel, Beha’alotecha 5676) speak of Moses’s time in Ethiopia. The medieval Midrash Yalkut Shimoni and the 17th century Yalkut Reuveni compiled by Rabbi Reuven Hoshke HaKohen also speak of Moses’s time ruling Ethiopia before he went to Midian.

But the origins of this legend date back to the second century BCE, hundreds of years before the Mishna and Talmud were compiled. The Jewish historian Artapanus, who lived in Egypt, most likely in Alexandria, wrote of Moses’s conquest of Ethiopia in his history book “Concerning The Jews.” Although the book no longer exists, Eusebius, who served as Bishop of Caesarea from 314 CE quotes sections of what Artapanus wrote about Moses. He describes how Pharaoh, named as Chenephres, sent Moses to lead an unskilled army against Ethiopia. Contrary to expectations Moses was victorious and founded the city of Hermopolis and taught the Ethiopian men to circumcise themselves.

Titus Flavius Josephus, the first century Jewish rebel turned Roman historian, gives more details of Moses in Ethiopia. He writes in The Antiquities of the Jews (Book II; chapter 10) that not only was Moses victorious but he also married an Ethiopian princess:

“Tharbis was the daughter of the king of the Ethiopians: she happened to see Moses as he led the army near the walls, and fought with great courage… she fell deeply in love with him; and upon the prevalancy of that passion, sent to him the most faithful of all her servants to discourse with him about their marriage. He thereupon accepted the offer, on condition she would procure the delivering up of the city…; and when Moses had cut off the Ethiopians, he gave thanks to God, and consummated his marriage, and led the Egyptians back to their own land.”

So, according to these ancient Jewish traditions, when Moses stood before God at the burning bush he was not merely a poor, humble shepherd, but also a former hero who had conquered foreign lands and ruled over them.

Yet at first Moses refused God’s command to go back to Israel and redeem the Israelites. Not only did he tell God he was unworthy, but he claimed that the people would not believe in him. And for doubting the faith of the nation Moses was punished.

Belief in a savior from afar does not require evidence or proof. When Moses returned to Egypt he performed the signs that God had given him, but it was unnecessary. For the verse states that immediately, “The people believed. And they heard that God had remembered the Children of Israel and that he had seen their suffering. And they bowed and prostrated themselves,” (Exodus 4:31).

The Torah tells us that Moses came from a distant land and brought the Israelites out of slavery. And just as the medieval faith in Prester John, the belief in a strong leader who will suddenly appear and save a nation remains powerful to this day.