In fact, I suspect that the only place people may have heard of Dawes is in “The Tipping Point,” where Malcolm Gladwell contrasts his failure with Revere’s success.

Gladwell uses Revere as a paradigm of a “connector” who can take an idea and turn it into an epidemic. He writes:

“When he died, his funeral was attended, in the words of one contemporary newspaper account, by ‘troops of people.’ He was a fisherman and a hunter, a cardplayer and a theater-lover, a frequenter of pubs and a successful businessman. He was active in the local Masonic Lodge and was a member of several select social clubs. He was also a doer, a man blessed — as David Hackett Fischer recounts in his brilliant book Paul Revere’s Ride — with an ‘uncanny genius for being at the center of events.’”

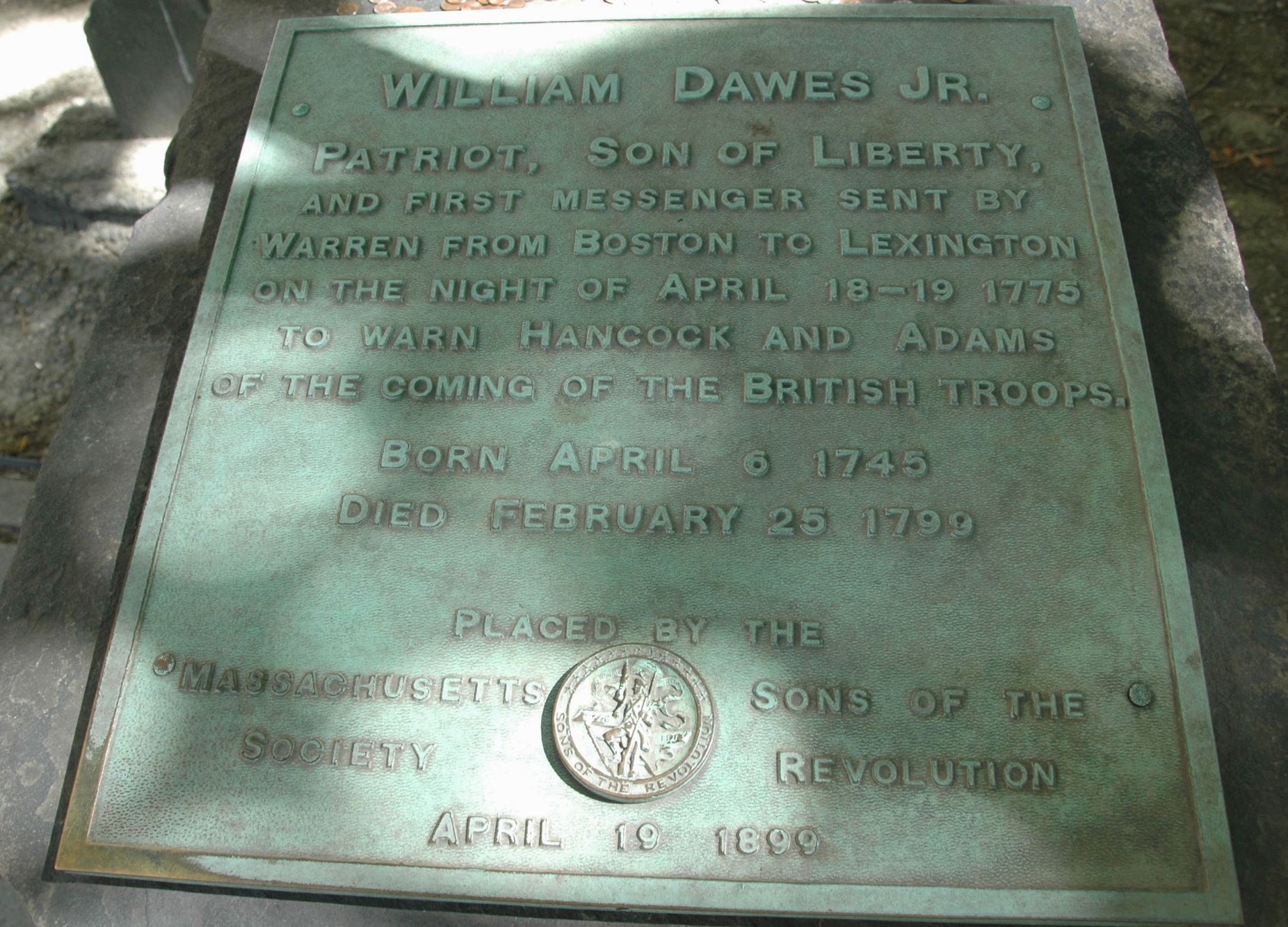

In contrast, nobody is certain what happened to Dawes after his midnight ride. Adding insult to injury, in 2007, it was discovered that he may not even be buried in his marked grave in Boston’s King’s Chapel Burying Ground, but may actually be buried five miles away with his wife.

Yet he was as much a patriot as Revere and played an equally important role in the revolutionary war.

While Revere was a silversmith, Dawes was a tanner. Both would have had a large number of contacts and connections. Dawes was so dedicated to independence that he boycotted British goods — the Boston Gazette stated that at his wedding, he wore a suit made entirely in America.

Like Revere and Dr Joseph Warren, who sent both messengers, Dawes was a Freemason. He had built up a large network of military connections. In October 1774, he led a group who brazenly stole two cannons from a British arsenal while the British soldiers were out at roll call. He often went out recruiting supporters for the colonial cause, sometimes taking his granddaughter with him, so that the British would not suspect he was up to anything untoward.

On the night of April 18, 1775, while Revere rowed across the Charles River in a boat, the 30-year-old Dawes was charged by Warren on the more dangerous overland route from Boston to Lexington to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams of the impending British invasion. His path required him to pass through a British-guarded checkpoint at Boston neck. Nobody knows for certain how he managed to get past the sentries, but it is likely that he had cultivated friendships with them for some time, preparing for just such an eventuality.

So why is Revere so famous while Dawes has been so forgotten (or maligned on the rare occasion he is mentioned)?

It is true that Revere knocked on doors along his journey to Lexington, waking the revolutionary soldiers and preparing them for the invasion, whereas Dawes rode directly to Hancock and Adams without stopping along the way (and, ironically, he was still beaten by Revere, who had a faster horse and a shorter route, and so was able to deliver the message before Dawes arrived). So, far fewer people were aware of Dawes’s daring ride.

But more likely Dawes was forgotten and Revere remembered due to the power of the written word. Dawes did not leave a record of his heroism, whereas Revere wrote three accounts of his ride, the last written 23 years after the event in a letter to Jeremy Belknap, Secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

And probably the most important reason that Dawes was forgotten by history is due to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s historically inaccurate poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Gladwell praises Revere and derides Dawes, writing: “This chapter is about the people critical to social epidemics and what makes someone like Paul Revere different from someone like William Dawes.” But one could equally argue that Revere’s fame was not because he was a better connector than Dawes, but simply because he got better coverage after the fact.

In contrast to the famous Revere and the forgotten Dawes, the Torah goes to great lengths to stress that the two revolutionary leaders who took the Israelites out of Egypt had different roles, yet were equals.

Moses was the chosen leader, but it was Aaron who was the social “connector” who could speak to both the downtrodden slaves and to Pharaoh. Moses was raised in Pharaoh’s palace, then fled the country, only to return decades later, at God’s command. In contrast, Aaron spent his entire life strengthening bonds between himself and others. Whereas Moses represented strict application of the law, described as “Let the judgment pierce the mountain,” (Midrash Shochar Tov on Psalms 90), Aaron embodied, “Love peace and pursue peace, love people and bring them close to Torah,” (Pirkei Avot 1:12).

Moses acknowledged his own shortcomings and God informed him that he could only succeed alongside his brother (Exodus 6:12-13).

Moses spoke before God saying, ‘Behold the Children of Israel did not listen to me, so how will Pharaoh listen to me?… So God spoke to Moses and Aaron and commanded them about the Children of Israel and about Pharaoh, king of Egypt, to take the Children of Israel out of the land of Egypt.,

In the following chapter (Exodus 7:1-2) the Torah makes it even more clear that their mission could only succeed with Aaron being the one to spread the word.

God said to Moses, see I have placed you as a god for Pharaoh, but Aaron your brother will be your prophet. You shall speak all that I command you, and Aaron your brother will speak to Pharaoh…

At some point, Moses found his voice and was able to speak directly to Pharaoh, and later on was also able to speak to the fledgling Jewish nation, becoming the law-bearer who informed them of all God’s decisions. And Aaron became an important figure in his own right, as the High Priest, such that he and his descendants had the task of acting as intermediaries between God and the Jewish people in the Temple rituals. The Torah stresses (Exodus 6:26-27) that both brothers were equally important, referring to them as a single person and switching the order of their names to show their co-leadership.

He is Aaron and Moses to whom God said, ‘Take the Children of Israel out of the land of Israel in their multitudes. They are the ones who speak to Pharaoh, king of Egypt, to take the Children of Israel from Egypt; he is Moses and Aaron.

But at the outset of their revolution, neither could have done it without the other.

No comments:

Post a Comment